Contemporary cosmological models are based on the idea that the

universe is pretty much the same everywhere - a stance sometimes

known as the Copernican principle. On the face of it, such

a claim seems preposterous; the center of the sun, for example,

bears little resemblance to the desolate cold of interstellar

space. But we take the Copernican principle to only apply on

the very largest scales, where local variations in density are

averaged over. Its validity on such scales is

manifested in a number of different observations, such as number counts

of galaxies and observations of diffuse X-ray and ![]() -ray

backgrounds, but is most clear in the 3° microwave background

radiation. Although we now know that the microwave background is not

perfectly smooth (and nobody ever expected that it was), the

deviations from regularity are on the order of 10-5 or less,

certainly an adequate basis for an approximate description of

spacetime on large scales.

-ray

backgrounds, but is most clear in the 3° microwave background

radiation. Although we now know that the microwave background is not

perfectly smooth (and nobody ever expected that it was), the

deviations from regularity are on the order of 10-5 or less,

certainly an adequate basis for an approximate description of

spacetime on large scales.

The Copernican principle is related to two more mathematically precise properties that a manifold might have: isotropy and homogeneity. Isotropy applies at some specific point in the space, and states that the space looks the same no matter what direction you look in. More formally, a manifold M is isotropic around a point p if, for any two vectors V and W in TpM, there is an isometry of M such that the pushforward of W under the isometry is parallel with V (not pushed forward). It is isotropy which is indicated by the observations of the microwave background.

Homogeneity is the statement that the metric is the same

throughout the space. In other words, given any two points p and

q in M, there is an isometry which takes p into

q. Note that there is no necessary relationship between homogeneity

and isotropy; a manifold can be homogeneous but nowhere isotropic

(such as

![]() × S2 in the usual metric), or it

can be isotropic

around a point without being homogeneous (such as a cone, which is

isotropic around its vertex but certainly not homogeneous). On the

other hand, if a space is isotropic everywhere then it is

homogeneous. (Likewise if it is isotropic around one point and

also homogeneous, it will be isotropic around every point.)

Since there is ample observational evidence for

isotropy, and the Copernican principle would have us believe that we

are not the center of the universe and therefore observers elsewhere

should also observe isotropy, we will henceforth assume both

homogeneity and isotropy.

× S2 in the usual metric), or it

can be isotropic

around a point without being homogeneous (such as a cone, which is

isotropic around its vertex but certainly not homogeneous). On the

other hand, if a space is isotropic everywhere then it is

homogeneous. (Likewise if it is isotropic around one point and

also homogeneous, it will be isotropic around every point.)

Since there is ample observational evidence for

isotropy, and the Copernican principle would have us believe that we

are not the center of the universe and therefore observers elsewhere

should also observe isotropy, we will henceforth assume both

homogeneity and isotropy.

There is one catch. When we look at distant galaxies, they appear

to be receding from us; the universe is apparently not static, but

changing with time. Therefore we begin construction of cosmological

models with the idea that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic

in space, but not in time. In general relativity this translates into

the statement that the universe can be foliated into spacelike slices

such that each slice is homogeneous and isotropic.

We therefore consider our spacetime to be

![]() ×

× ![]() , where

, where

![]() represents the time direction and

represents the time direction and ![]() is a homogeneous and

isotropic three-manifold. The usefulness of homogeneity and

isotropy is that they imply that

is a homogeneous and

isotropic three-manifold. The usefulness of homogeneity and

isotropy is that they imply that ![]() must be a maximally

symmetric space. (Think of isotropy as invariance under rotations,

and homogeneity as invariance under translations. Then homogeneity

and isotropy together imply that a space has its maximum possible

number of Killing vectors.) Therefore

we can take our metric to be of the form

must be a maximally

symmetric space. (Think of isotropy as invariance under rotations,

and homogeneity as invariance under translations. Then homogeneity

and isotropy together imply that a space has its maximum possible

number of Killing vectors.) Therefore

we can take our metric to be of the form

| (8.1) |

Here t is the timelike coordinate, and

(u1, u2, u3) are the

coordinates on ![]() ;

;

![]() is the maximally symmetric

metric on

is the maximally symmetric

metric on ![]() . This formula is a special case of (7.2), which we

used to derive the Schwarzschild metric, except we have scaled t

such that gtt = - 1. The function a(t)

is known as the

scale factor, and it tells us "how big" the spacelike

slice

. This formula is a special case of (7.2), which we

used to derive the Schwarzschild metric, except we have scaled t

such that gtt = - 1. The function a(t)

is known as the

scale factor, and it tells us "how big" the spacelike

slice ![]() is at the moment t. The coordinates used here,

in which the metric is free of cross terms

dt dui and the

spacelike components are proportional to a single function of t, are

known as comoving coordinates, and an observer who stays at constant

ui is also called "comoving". Only a comoving

observer will

think that the universe looks isotropic; in fact on Earth we are

not quite comoving, and as a result we see a dipole anisotropy in

the cosmic microwave background as a result of the conventional

Doppler effect.

is at the moment t. The coordinates used here,

in which the metric is free of cross terms

dt dui and the

spacelike components are proportional to a single function of t, are

known as comoving coordinates, and an observer who stays at constant

ui is also called "comoving". Only a comoving

observer will

think that the universe looks isotropic; in fact on Earth we are

not quite comoving, and as a result we see a dipole anisotropy in

the cosmic microwave background as a result of the conventional

Doppler effect.

Our interest is therefore in maximally symmetric Euclidean three-metrics

![]() . We know that maximally symmetric metrics

obey

. We know that maximally symmetric metrics

obey

| (8.2) |

where k is some constant, and we put a superscript (3) on

the Riemann tensor to remind us that it is associated with the

three-metric

![]() , not the metric of the entire spacetime.

The Ricci tensor is then

, not the metric of the entire spacetime.

The Ricci tensor is then

| (8.3) |

If the space is to be maximally symmetric, then it will certainly be spherically symmetric. We already know something about spherically symmetric spaces from our exploration of the Schwarzschild solution; the metric can be put in the form

| (8.4) |

The components of the Ricci tensor for such a metric can be obtained

from (7.16), the Ricci tensor for a spherically symmetric spacetime,

by setting ![]() = 0 and

= 0 and

![]()

![]() = 0, which gives

= 0, which gives

| (8.5) |

We set these proportional to the metric using (8.3), and can solve

for ![]() (r):

(r):

| (8.6) |

This gives us the following metric on spacetime:

| (8.7) |

This is the Robertson-Walker metric. We have not yet made use of Einstein's equations; those will determine the behavior of the scale factor a(t).

Note that the substitutions

| (8.8) |

leave (8.7) invariant. Therefore the only relevant parameter

is k/| k|, and there are three cases of interest: k

= - 1,

k = 0, and k = + 1. The k = - 1 case corresponds

to constant

negative curvature on ![]() , and is called open; the

k = 0 case corresponds to no curvature on

, and is called open; the

k = 0 case corresponds to no curvature on ![]() , and is called

flat; the k = + 1 case corresponds to positive curvature

on

, and is called

flat; the k = + 1 case corresponds to positive curvature

on ![]() ,

and is called closed.

,

and is called closed.

Let us examine each of these possibilities. For the flat case

k = 0 the metric on ![]() is

is

| (8.9) |

which is simply flat Euclidean space. Globally, it could describe

![]() or a more complicated manifold, such as the

three-torus S1 × S1 ×

S1. For the closed case k = + 1 we can define

r = sin

or a more complicated manifold, such as the

three-torus S1 × S1 ×

S1. For the closed case k = + 1 we can define

r = sin![]() to write the metric on

to write the metric on ![]() as

as

| (8.10) |

which is the metric of a three-sphere. In this case the only

possible global structure is actually the three-sphere (except for

the non-orientable manifold ![]() P3). Finally in the open k = - 1

case we can set

r = sinh

P3). Finally in the open k = - 1

case we can set

r = sinh![]() to obtain

to obtain

| (8.11) |

This is the metric for a three-dimensional space of constant negative curvature; it is hard to visualize, but think of the saddle example we spoke of in Section Three. Globally such a space could extend forever (which is the origin of the word "open"), but it could also describe a non-simply-connected compact space (so "open" is really not the most accurate description).

With the metric in hand, we can set about computing the connection

coefficients and curvature tensor. Setting

![]()

![]() da/dt,

the Christoffel symbols are given by

da/dt,

the Christoffel symbols are given by

| (8.12) |

The nonzero components of the Ricci tensor are

| (8.13) |

and the Ricci scalar is then

| (8.14) |

The universe is not empty, so we are not interested in vacuum solutions to Einstein's equations. We will choose to model the matter and energy in the universe by a perfect fluid. We discussed perfect fluids in Section One, where they were defined as fluids which are isotropic in their rest frame. The energy-momentum tensor for a perfect fluid can be written

| (8.15) |

where ![]() and p are the energy density and pressure

(respectively)

as measured in the rest frame, and U

and p are the energy density and pressure

(respectively)

as measured in the rest frame, and U![]() is the four-velocity of

the fluid. It is clear that, if a fluid which is isotropic in some

frame leads to a metric which is isotropic in some frame, the two

frames will coincide; that is, the fluid will be at rest in comoving

coordinates. The four-velocity is then

is the four-velocity of

the fluid. It is clear that, if a fluid which is isotropic in some

frame leads to a metric which is isotropic in some frame, the two

frames will coincide; that is, the fluid will be at rest in comoving

coordinates. The four-velocity is then

| (8.16) |

and the energy-momentum tensor is

| (8.17) |

With one index raised this takes the more convenient form

| (8.18) |

Note that the trace is given by

| (8.19) |

Before plugging in to Einstein's equations, it is educational to consider the zero component of the conservation of energy equation:

| (8.20) |

To make progress it is necessary to choose an equation of

state, a relationship between ![]() and p. Essentially all of

the perfect fluids relevant to cosmology obey the simple equation

of state

and p. Essentially all of

the perfect fluids relevant to cosmology obey the simple equation

of state

| (8.21) |

where w is a constant independent of time. The conservation of energy equation becomes

| (8.22) |

which can be integrated to obtain

| (8.23) |

The two most popular examples of cosmological fluids are known as dust and radiation. Dust is collisionless, nonrelativistic matter, which obeys w = 0. Examples include ordinary stars and galaxies, for which the pressure is negligible in comparison with the energy density. Dust is also known as "matter", and universes whose energy density is mostly due to dust are known as matter-dominated. The energy density in matter falls off as

| (8.24) |

This is simply interpreted

as the decrease in the number density of particles as the universe

expands. (For dust the energy density is dominated by the rest

energy, which is proportional to the number density.) "Radiation"

may be used to describe either actual electromagnetic radiation, or

massive particles moving at relative velocities sufficiently close to

the speed of light that they become indistinguishable from photons (at

least as far as their equation of state is concerned).

Although radiation is a perfect fluid and thus has an energy-momentum

tensor given by (8.15), we also know that

T![]()

![]() can be expressed in

terms of the field strength as

can be expressed in

terms of the field strength as

| (8.25) |

The trace of this is given by

| (8.26) |

But this must also equal (8.19), so the equation of state is

| (8.27) |

A universe in which most of the energy density is in the form of radiation is known as radiation-dominated. The energy density in radiation falls off as

| (8.28) |

Thus, the energy density in radiation falls off slightly faster

than that in matter; this is because the number density of photons

decreases in the same way as the number density of nonrelativistic

particles, but individual photons also lose energy as a-1

as they redshift, as we will see later. (Likewise, massive but

relativistic particles will lose energy as they "slow down" in

comoving coordinates.) We believe that today the

energy density of the universe is dominated by matter, with

![]() /

/![]()

![]() 106. However, in the past

the universe was much smaller, and the energy density in radiation

would have dominated at very early times.

106. However, in the past

the universe was much smaller, and the energy density in radiation

would have dominated at very early times.

There is one other form of energy-momentum that is sometimes considered, namely that of the vacuum itself. Introducing energy into the vacuum is equivalent to introducing a cosmological constant. Einstein's equations with a cosmological constant are

| (8.29) |

which is clearly the same form as the equations with no cosmological constant but an energy-momentum tensor for the vacuum,

| (8.30) |

This has the form of a perfect fluid with

| (8.31) |

We therefore have w = - 1, and the energy density is independent of a, which is what we would expect for the energy density of the vacuum. Since the energy density in matter and radiation decreases as the universe expands, if there is a nonzero vacuum energy it tends to win out over the long term (as long as the universe doesn't start contracting). If this happens, we say that the universe becomes vacuum-dominated.

We now turn to Einstein's equations. Recall that they can be written in the form (4.45):

| (8.32) |

The

![]()

![]() = 00 equation is

= 00 equation is

| (8.33) |

and the

![]()

![]() = ij equations give

= ij equations give

| (8.34) |

(There is only one distinct equation from

![]()

![]() = ij, due to

isotropy.) We can use (8.33) to eliminate second derivatives in

(8.34), and do a little cleaning up to obtain

= ij, due to

isotropy.) We can use (8.33) to eliminate second derivatives in

(8.34), and do a little cleaning up to obtain

| (8.35) |

and

| (8.36) |

Together these are known as the Friedmann equations, and metrics of the form (8.7) which obey these equations define Friedmann-Robertson-Walker (FRW) universes.

There is a bunch of terminology which is associated with the cosmological parameters, and we will just introduce the basics here. The rate of expansion is characterized by the Hubble parameter,

| (8.37) |

The value of the Hubble parameter at the present epoch is the

Hubble constant, H0. There is currently a great deal of

controversy about what its actual value is, with measurements

falling in the range of 40 to 90 km/sec/Mpc. ("Mpc" stands for

"megaparsec", which is

3 × 1024 cm.) Note that we

have to divide ![]() by a to get a measurable quantity, since

the overall scale of a is irrelevant. There is also the

deceleration parameter,

by a to get a measurable quantity, since

the overall scale of a is irrelevant. There is also the

deceleration parameter,

| (8.38) |

which measures the rate of change of the rate of expansion.

Another useful quantity is the density parameter,

| (8.39) |

where the critical density is defined by

| (8.40) |

This quantity (which will generally change with time) is called the "critical" density because the Friedmann equation (8.36) can be written

| (8.41) |

The sign of k is therefore determined by whether ![]() is

greater than, equal to, or less than one. We have

is

greater than, equal to, or less than one. We have

|

The density parameter, then, tells us which of the three Robertson-Walker geometries describes our universe. Determining it observationally is an area of intense investigation.

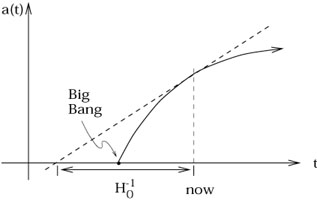

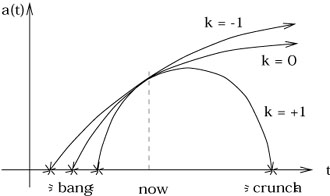

It is possible to solve the Friedmann equations exactly in

various simple cases, but it is often more useful to know

the qualitative behavior of various possibilities. Let us for

the moment set ![]() = 0, and consider the behavior of universes

filled with fluids of positive energy (

= 0, and consider the behavior of universes

filled with fluids of positive energy (![]() > 0) and nonnegative

pressure (p

> 0) and nonnegative

pressure (p ![]() 0). Then by (8.35) we must have

0). Then by (8.35) we must have ![]() < 0.

Since we know from observations of distant galaxies that

the universe is expanding (

< 0.

Since we know from observations of distant galaxies that

the universe is expanding (![]() > 0),

this means that the universe is "decelerating." This is what

we should expect, since the gravitational attraction of the matter

in the universe works against the expansion. The fact that

the universe can only decelerate means that it must have been

expanding even faster in the past; if we trace the evolution

backwards in time, we necessarily reach a singularity at

a = 0. Notice that if

> 0),

this means that the universe is "decelerating." This is what

we should expect, since the gravitational attraction of the matter

in the universe works against the expansion. The fact that

the universe can only decelerate means that it must have been

expanding even faster in the past; if we trace the evolution

backwards in time, we necessarily reach a singularity at

a = 0. Notice that if ![]() were exactly zero, a(t)

would be a straight line, and the age of the universe would be

H0-1. Since

were exactly zero, a(t)

would be a straight line, and the age of the universe would be

H0-1. Since ![]() is actually negative, the universe

must be somewhat younger than that.

is actually negative, the universe

must be somewhat younger than that.

|

This singularity at a = 0 is the Big Bang.

It represents the creation of the universe from a singular state,

not explosion of matter into a pre-existing spacetime. It might be

hoped that the perfect symmetry of our FRW universes was responsible

for this singularity, but in fact it's not true; the singularity

theorems predict that any universe with ![]() > 0 and p

> 0 and p ![]() 0 must

have begun at a singularity. Of course

the energy density becomes arbitrarily high as

a

0 must

have begun at a singularity. Of course

the energy density becomes arbitrarily high as

a ![]() 0,

and we don't expect classical general relativity to be an

accurate description of nature in this regime; hopefully a

consistent theory of quantum gravity will be able to fix things up.

0,

and we don't expect classical general relativity to be an

accurate description of nature in this regime; hopefully a

consistent theory of quantum gravity will be able to fix things up.

The future evolution is different for different values of k.

For the open and flat cases, k ![]() 0, (8.36) implies

0, (8.36) implies

| (8.42) |

The right hand side is strictly positive (since we are

assuming ![]() > 0), so

> 0), so ![]() never passes through zero. Since

we know that today

never passes through zero. Since

we know that today ![]() > 0, it must be positive for all time.

Thus, the open and flat universes expand forever - they are

temporally as well as spatially open. (Please keep

in mind what assumptions go into this - namely, that there

is a nonzero positive energy density. Negative energy density

universes do not have to expand forever, even if they are "open".)

> 0, it must be positive for all time.

Thus, the open and flat universes expand forever - they are

temporally as well as spatially open. (Please keep

in mind what assumptions go into this - namely, that there

is a nonzero positive energy density. Negative energy density

universes do not have to expand forever, even if they are "open".)

How fast do these universes keep expanding? Consider the

quantity ![]() a3 (which is constant in matter-dominated

universes). By the conservation of energy equation (8.20) we have

a3 (which is constant in matter-dominated

universes). By the conservation of energy equation (8.20) we have

| (8.43) |

The right hand side is either zero or negative; therefore

| (8.44) |

This implies in turn that ![]() a2 must go to zero in an

ever-expanding universe, where

a

a2 must go to zero in an

ever-expanding universe, where

a ![]()

![]() . Thus (8.42)

tells us that

. Thus (8.42)

tells us that

| (8.45) |

(Remember that this is true for k ![]() 0.) Thus, for k = - 1

the expansion approaches the limiting value

0.) Thus, for k = - 1

the expansion approaches the limiting value

![]()

![]() 1,

while for k = 0 the universe keeps expanding, but more and more

slowly.

1,

while for k = 0 the universe keeps expanding, but more and more

slowly.

For the closed universes (k = + 1), (8.36) becomes

| (8.46) |

The argument that

![]() a2

a2 ![]() 0 as

a

0 as

a ![]()

![]() still applies; but in that case (8.46) would become negative, which

can't happen. Therefore the universe does not expand indefinitely;

a possesses an upper bound

amax. As a approaches

amax, (8.35) implies

still applies; but in that case (8.46) would become negative, which

can't happen. Therefore the universe does not expand indefinitely;

a possesses an upper bound

amax. As a approaches

amax, (8.35) implies

| (8.47) |

Thus ![]() is finite and negative at this point, so a

reaches

amax and starts decreasing, whereupon (since

is finite and negative at this point, so a

reaches

amax and starts decreasing, whereupon (since

![]() < 0)

it will inevitably continue to contract to zero - the Big Crunch.

Thus, the closed universes (again, under our assumptions of

positive

< 0)

it will inevitably continue to contract to zero - the Big Crunch.

Thus, the closed universes (again, under our assumptions of

positive ![]() and nonnegative p) are closed in time as well

as space.

and nonnegative p) are closed in time as well

as space.

|

We will now list some of the exact solutions corresponding to

only one type of energy density.

For dust-only universes (p = 0), it is convenient to define

a development angle ![]() (t), rather than using t as

a parameter directly. The solutions are then, for open

universes,

(t), rather than using t as

a parameter directly. The solutions are then, for open

universes,

| (8.48) |

for flat universes,

| (8.49) |

and for closed universes,

| (8.50) |

where we have defined

| (8.51) |

For universes filled with nothing but radiation,

p = ![]()

![]() ,

we have once again open universes,

,

we have once again open universes,

| (8.52) |

flat universes,

| (8.53) |

and closed universes,

| (8.54) |

where this time we defined

| (8.55) |

You can check for yourselves that these exact solutions have the properties we argued would hold in general.

For universes which are empty save for the cosmological constant,

either ![]() or p will be negative, in violation of the

assumptions we used earlier to derive the general behavior of

a(t). In this case the connection between open/closed and

expands forever/recollapses is lost. We begin by considering

or p will be negative, in violation of the

assumptions we used earlier to derive the general behavior of

a(t). In this case the connection between open/closed and

expands forever/recollapses is lost. We begin by considering

![]() < 0. In this case

< 0. In this case ![]() is negative, and from (8.41) this can only happen if k = - 1.

The solution in this case is

is negative, and from (8.41) this can only happen if k = - 1.

The solution in this case is

| (8.56) |

There is also an open (k = - 1) solution for ![]() > 0, given by

> 0, given by

| (8.57) |

A flat vacuum-dominated universe must have ![]() > 0, and the

solution is

> 0, and the

solution is

| (8.58) |

while the closed universe must also have ![]() > 0, and satisfies

> 0, and satisfies

| (8.59) |

These solutions are a little misleading. In fact the three

solutions for ![]() > 0 - (8.57), (8.58), and (8.59) -

all represent the same spacetime, just in different coordinates.

This spacetime, known as de Sitter space, is actually

maximally symmetric as a spacetime. (See Hawking and Ellis for

details.) The

> 0 - (8.57), (8.58), and (8.59) -

all represent the same spacetime, just in different coordinates.

This spacetime, known as de Sitter space, is actually

maximally symmetric as a spacetime. (See Hawking and Ellis for

details.) The ![]() < 0 solution (8.56) is

also maximally symmetric, and is known as anti-de Sitter space.

< 0 solution (8.56) is

also maximally symmetric, and is known as anti-de Sitter space.

It is clear that we would like to observationally determine a

number of quantities to decide which of the FRW models

corresponds to our universe. Obviously we would like to determine

H0, since that is related to the age of the universe.

(For a

purely matter-dominated, k = 0 universe, (8.49) implies that the

age is 2 / (3H0). Other possibilities would predict

similar relations.) We would also like to know ![]() , which determines

k through (8.41). Given the definition (8.39) of

, which determines

k through (8.41). Given the definition (8.39) of ![]() ,

this means we want to know both H0 and

,

this means we want to know both H0 and ![]() . Unfortunately

both quantities are hard to measure accurately, especially

. Unfortunately

both quantities are hard to measure accurately, especially ![]() .

But notice that the deceleration parameter q can be related

to

.

But notice that the deceleration parameter q can be related

to ![]() using (8.35):

using (8.35):

| (8.60) |

Therefore, if we think we know what w is (i.e., what kind

of stuff the universe is made of), we can determine ![]() by

measuring q. (Unfortunately we are not completely confident that

we know w, and q is itself hard to measure. But people are

trying.)

by

measuring q. (Unfortunately we are not completely confident that

we know w, and q is itself hard to measure. But people are

trying.)

To understand how these quantities might conceivably be measured,

let's consider geodesic motion in an FRW universe. There are a

number of spacelike Killing vectors, but no timelike Killing vector

to give us a notion of conserved energy. There is, however, a

Killing tensor. If

U![]() = (1, 0, 0, 0) is the four-velocity of

comoving observers, then the tensor

= (1, 0, 0, 0) is the four-velocity of

comoving observers, then the tensor

| (8.61) |

satisfies

![]() K

K![]()

![]() ) = 0 (as you can check), and is

therefore a Killing tensor. This means that if a particle has

four-velocity

V

) = 0 (as you can check), and is

therefore a Killing tensor. This means that if a particle has

four-velocity

V![]() = dx

= dx![]() /d

/d![]() , the quantity

, the quantity

| (8.62) |

will be a constant along geodesics. Let's think about this, first

for massive particles. Then we will have

V![]() V

V![]() = - 1, or

= - 1, or

| (8.63) |

where

|![]() |2 =

gijViVj. So

(8.61) implies

|2 =

gijViVj. So

(8.61) implies

| (8.64) |

The particle therefore "slows down" with respect to the comoving coordinates as the universe expands. In fact this is an actual slowing down, in the sense that a gas of particles with initially high relative velocities will cool down as the universe expands.

A similar thing happens to null geodesics. In this case

V![]() V

V![]() = 0, and (8.62) implies

= 0, and (8.62) implies

| (8.65) |

But the frequency of the photon as measured by a comoving

observer is

![]() = - U

= - U![]() V

V![]() . The frequency of the photon

emitted with frequency

. The frequency of the photon

emitted with frequency ![]() will therefore be observed with

a lower frequency

will therefore be observed with

a lower frequency ![]() as the universe expands:

as the universe expands:

| (8.66) |

Cosmologists like to speak of this in terms of the redshift z between the two events, defined by the fractional change in wavelength:

| (8.67) |

Notice that this redshift is not the same as the conventional Doppler effect; it is the expansion of space, not the relative velocities of the observer and emitter, which leads to the redshift.

The redshift is something we can measure; we know the rest-frame wavelengths of various spectral lines in the radiation from distant galaxies, so we can tell how much their wavelengths have changed along the path from time t1 when they were emitted to time t0 when they were observed. We therefore know the ratio of the scale factors at these two times. But we don't know the times themselves; the photons are not clever enough to tell us how much coordinate time has elapsed on their journey. We have to work harder to extract this information.

Roughly speaking, since a photon moves at the speed of light its travel time should simply be its distance. But what is the "distance" of a far away galaxy in an expanding universe? The comoving distance is not especially useful, since it is not measurable, and furthermore because the galaxies need not be comoving in general. Instead we can define the luminosity distance as

| (8.68) |

where L is the absolute luminosity of the source and F is

the flux measured by the observer (the energy per unit time per

unit area of some detector). The definition comes from the

fact that in flat space, for a source at distance d the flux

over the luminosity is just one over the area of a sphere centered

around the source,

F/L = 1/A(d )= 1/4![]() d2. In an FRW universe,

however, the flux will be diluted. Conservation of photons

tells us that the total number of photons emitted by

the source will eventually pass through a sphere at comoving

distance r from the emitter. Such a sphere is at a physical

distance d = a0r, where

a0 is the scale factor when the photons

are observed. But the flux is diluted by two additional effects:

the individual photons redshift by a factor (1 + z), and the photons

hit the sphere less frequently, since two photons emitted a time

d2. In an FRW universe,

however, the flux will be diluted. Conservation of photons

tells us that the total number of photons emitted by

the source will eventually pass through a sphere at comoving

distance r from the emitter. Such a sphere is at a physical

distance d = a0r, where

a0 is the scale factor when the photons

are observed. But the flux is diluted by two additional effects:

the individual photons redshift by a factor (1 + z), and the photons

hit the sphere less frequently, since two photons emitted a time

![]() t apart will be measured at a time

(1 + z)

t apart will be measured at a time

(1 + z)![]() t apart.

Therefore we will have

t apart.

Therefore we will have

| (8.69) |

or

| (8.70) |

The luminosity distance dL is something we might hope to measure, since there are some astrophysical sources whose absolute luminosities are known ("standard candles"). But r is not observable, so we have to remove that from our equation. On a null geodesic (chosen to be radial for convenience) we have

| (8.71) |

or

| (8.72) |

For galaxies not too far away, we can expand the scale factor in a Taylor series about its present value:

| (8.73) |

We can then expand both sides of (8.72) to find

| (8.74) |

Now remembering (8.67), the expansion (8.73) is the same as

| (8.75) |

For small H0(t1 - t0) this can be inverted to yield

| (8.76) |

Substituting this back again into (8.74) gives

| (8.77) |

Finally, using this in (8.70) yields Hubble's Law:

| (8.78) |

Therefore, measurement of the luminosity distances and redshifts of a sufficient number of galaxies allows us to determine H0 and q0, and therefore takes us a long way to deciding what kind of FRW universe we live in. The observations themselves are extremely difficult, and the values of these parameters in the real world are still hotly contested. Over the next decade or so a variety of new strategies and more precise application of old strategies could very well answer these questions once and for all.