C. Inflation and Scalar Fields

As stated above, inflation is capable of solving many of the

initial value, or `fine-tuning', problems of the hot Big Bang

model. This is assuming that there is some mechanism to bring

about the negative pressure state needed for quasi-exponential

growth of the scale factor. In the early 1980's, Alan Guth

[33]

was studying properties of grand unified theories or

GUTs. He noticed that these theories predict a large number of

topological defects. Specifically, he was addressing the issue of

monopole creation in the SU(5) GUT. He found the theory predicts a

large number of these monopoles, and that they should `over-close'

the universe. This means that the monopole contribution to

is greater than the observed

upper-bound on the density

parameter,

is greater than the observed

upper-bound on the density

parameter,  > 4, which comes from observation

[5]. To remedy this,

Guth concluded that the symmetry breaking associated with scalar

fields in the particle theory must cause the universe to enter a

period of rapid expansion. This expansion `dilutes' the density

of the monopoles created, as stated above.

> 4, which comes from observation

[5]. To remedy this,

Guth concluded that the symmetry breaking associated with scalar

fields in the particle theory must cause the universe to enter a

period of rapid expansion. This expansion `dilutes' the density

of the monopoles created, as stated above.

The first step in understanding the dynamics of scalar fields is

to undertake the study of field theory. In field theory, one

considers a Lagrangian density, as opposed to the usual Lagrangian

from classical mechanics. This is because the scalar field is

taken to be a continuous field, whereas the Lagrangian in

mechanics is usually based on discrete particle systems. The

Lagrangian (L) is related to the Lagrangian density

( ) by,

) by,

Usually the scalar field is represented by a continuous function,

(x, t), which can be real or

complex. Given a potential

density of the field, V(

(x, t), which can be real or

complex. Given a potential

density of the field, V( ),

),

takes the form,

takes the form,

The resulting Euler-Lagrange equations result from varying the action with respect to spacetime [41],

where xµ = (t, -xi) as

usual, and  = c = 1. Also note,

gµ

= c = 1. Also note,

gµ = diag(1,

-1, -1, -1), the factor of

= diag(1,

-1, -1, -1), the factor of  -g

that usually appears in the action and other equations involving

tensor densities will be sqrt[-(-1)] = 1 (Minkowski space). The

resulting equation is

-g

that usually appears in the action and other equations involving

tensor densities will be sqrt[-(-1)] = 1 (Minkowski space). The

resulting equation is

The prime represents differentiation with respect to

and

the term containing the Hubble constant serves as a kind of

friction term resulting from the expansion. The field is taken to

be homogeneous, which eliminates any gradient contributions. This

homogeneity is a safe assumption, since physical gradients

are related to comoving gradients by the scale factor,

and

the term containing the Hubble constant serves as a kind of

friction term resulting from the expansion. The field is taken to

be homogeneous, which eliminates any gradient contributions. This

homogeneity is a safe assumption, since physical gradients

are related to comoving gradients by the scale factor,

Thus, the inhomogeneities in the field are redshifted away during inflation since the scale factor increases by a large amount.

One can also define the stress-energy tensor by use of Noether's theorem [41],

This is useful, because it can be compared to

Tµ for a

perfect fluid, namely,

for a

perfect fluid, namely,

The calculation for the pressure is a bit more subtle,

Consider the first component of pressure, again making use of (53) and (57),

Since g11 = -1 and one can use the metric to raise and lower indices,

Since the metric is diagonal this yields,

Similarly, the T22 and T33 components may be found. So for the total pressure one finds,

or,

From the T00 component we already found,

Equations (58), (59) for the pressure and

the energy density, show that the equation, p =

- is not quite

satisfied. A first resolution to this problem is to again assume

that the scalar field (

is not quite

satisfied. A first resolution to this problem is to again assume

that the scalar field ( ) is

spatially homogeneous, allowing

one to eliminate the gradient terms

(

) is

spatially homogeneous, allowing

one to eliminate the gradient terms

(

). This

assumption is only made at this point to simplify the analysis. As

we have seen if one keeps the terms, it can be shown that the

gradients are redshifted away by the expansion (56).

Ignoring gradients, the equations become

). This

assumption is only made at this point to simplify the analysis. As

we have seen if one keeps the terms, it can be shown that the

gradients are redshifted away by the expansion (56).

Ignoring gradients, the equations become

The first term 1/2

2 can be thought of as

the kinetic energy and the second as the potential, or

configuration energy. It is now possible to explicitly see where

Equation (55) came from if we assume the field can

be described as a `perfect' fluid. This assumption allows us to

use a continuity equation,

2 can be thought of as

the kinetic energy and the second as the potential, or

configuration energy. It is now possible to explicitly see where

Equation (55) came from if we assume the field can

be described as a `perfect' fluid. This assumption allows us to

use a continuity equation,

By plugging in the energy density of the field (61) and making use of the Friedmann equation (to get H) one obtains Equation (55) in perhaps a more enlightening way.

From the pressure and energy density derived above, we see that

the requirement that p =

- can be

approximately met, if one

requires

can be

approximately met, if one

requires  <<

V(

<<

V( ). This leads to what is

called the

slow-roll approximation (SRA), which provides a natural condition

for inflation to occur

(25)

To assure the constraint on

). This leads to what is

called the

slow-roll approximation (SRA), which provides a natural condition

for inflation to occur

(25)

To assure the constraint on

, one must also require that

, one must also require that

be

negligible. Given these requirements, we will to define the

slow-roll parameters and introduce the Planck mass

(26)

[46],

be

negligible. Given these requirements, we will to define the

slow-roll parameters and introduce the Planck mass

(26)

[46],

At this point, it is useful to distinguish

as the inflaton

field. Inflaton is the name given to

as the inflaton

field. Inflaton is the name given to

, since its origin does

not have to originate with a specified particle theory. Although

the original hope was that

, since its origin does

not have to originate with a specified particle theory. Although

the original hope was that  would

help determine the correct

particle physics models, current model building does not

necessarily require specific particle phenomenology. This is

actually an advantage for inflation, it retains its power to solve

the initial value problems, yet it could arise from any arbitrary

source (i.e., any arbitrary inflaton).

would

help determine the correct

particle physics models, current model building does not

necessarily require specific particle phenomenology. This is

actually an advantage for inflation, it retains its power to solve

the initial value problems, yet it could arise from any arbitrary

source (i.e., any arbitrary inflaton).

However, observation of the large-scale structure of the universe and anisotropies in the cosmic background should be able to constrain the inflaton parameters to a particular region. This can then be used by particle theorists, as a motivation for some required scalar field. Observational aspects of inflation will be considered in the next section, but this property of the inflaton field manifests itself as one of the greatest contributions of cosmology commensurate with particle theory. Some examples of potentials that have been proposed for the inflaton are presented below [47], [29].

In Guth's original inflation scenario

[33],

the inflaton

field ( ) sits at a local minimum

and is trapped in a false

vacuum state (see Figure 7). The vacuum state of

a field

or particle is the lowest energy state available to the system.

Some examples are the ground state of the hydrogen atom (-13.6 eV)

and the ground state of the harmonic oscillator (1/2

) sits at a local minimum

and is trapped in a false

vacuum state (see Figure 7). The vacuum state of

a field

or particle is the lowest energy state available to the system.

Some examples are the ground state of the hydrogen atom (-13.6 eV)

and the ground state of the harmonic oscillator (1/2

). The concept of `false'

vacuum comes from examination of

Figure 7. If

). The concept of `false'

vacuum comes from examination of

Figure 7. If

is `placed' in the potential well on

the left, the lowest energy available is that of the false vacuum.

The only way

is `placed' in the potential well on

the left, the lowest energy available is that of the false vacuum.

The only way  can get out of this

local minimum is by

quantum tunneling, after some characteristic time. As tunneling

takes place the universe inflates. Inflation halts when

can get out of this

local minimum is by

quantum tunneling, after some characteristic time. As tunneling

takes place the universe inflates. Inflation halts when

reaches the false vacuum and bubbles of the false vacuum coalesce

releasing the `latent' heat that was stored in the field. This is

much like the way bubble nucleation occurs when opening a bottle

of compressed liquid (like soda). Energy escapes from the soda in

the form of carbon dioxide and the liquid enters a lower more

favorable energy state.

reaches the false vacuum and bubbles of the false vacuum coalesce

releasing the `latent' heat that was stored in the field. This is

much like the way bubble nucleation occurs when opening a bottle

of compressed liquid (like soda). Energy escapes from the soda in

the form of carbon dioxide and the liquid enters a lower more

favorable energy state.

Tunneling that leads to bubble nucleation is a first order phase transition. This is very similar to processes that take place in the study of condensed matter physics, fluid dynamics, and ferromagnetism (see for example [48] and [49]). The bubbles experience a state of negative pressure. Once created, they continue to expand at an exponential rate. Each expanding bubble corresponds to an expanding domain. However, when one carefully investigates this situation, one finds that the bubbles can collide as they reach the false vacuum. Furthermore, the size of these bubbles expands at too great of a rate and the corresponding universe is left void of structure. One finds that too much inflation occurs and the visible universe is left empty. This is referred to as the `graceful exit' problem. Again one is presented with an empty universe, which was the same reason that the DeSitter universe idea was abandoned.

Guth and others further tried to remedy these problems by

fine-tuning the bubble formation. The problem with this is two

fold. One, cosmologists and particle theorists don't like

fine-tuning. The idea is to form a model that gives our universe

as a usual result that follows from natural consequences. By

natural one means that the scales of the model are related to the

fundamental constants of nature; e.g., quantum gravity should

occur at the Planck scale, since this scale is the only one

natural in units (c,  ,

G). Secondly, if the model is

fine-tuned to agree with the observations of the anisotropies in

the cosmic background, the bubbles would collide far too often.

This results in the appearance of topological defects, like the

monopoles. However, this was the whole reason inflation was

invoked in the first place.

,

G). Secondly, if the model is

fine-tuned to agree with the observations of the anisotropies in

the cosmic background, the bubbles would collide far too often.

This results in the appearance of topological defects, like the

monopoles. However, this was the whole reason inflation was

invoked in the first place.

In 1982, a solution to the graceful exit problem was proposed by

Linde [50]

and independently by Steinhardt and Albrecht

[51].

This New Inflation model solves the

graceful exit problem by assuming the inflaton field evolves very

slowly from its initial state, while undergoing a phase transition

of second order. Figure 8 illustrates this by again

considering the evolution of  . If

. If

`rolls' down the

potential at a slow rate, one obtains the amount of inflation

needed to solve the initial value problems. After the universe

cools to a critical temperature, Tc,

`rolls' down the

potential at a slow rate, one obtains the amount of inflation

needed to solve the initial value problems. After the universe

cools to a critical temperature, Tc,

can proceed to

its `true' vacuum state energy. The transition of the potential

is a second order phase transition, so this model does not require

tunneling [42].

This type of transition is similar to

the transitions that occur in ferromagnetic systems

[49].

can proceed to

its `true' vacuum state energy. The transition of the potential

is a second order phase transition, so this model does not require

tunneling [42].

This type of transition is similar to

the transitions that occur in ferromagnetic systems

[49].

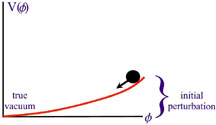

The majority of current models rely on another concept coined by Linde as Chaotic Inflation. This model differs from Old and New Inflation in that no phase transitions occur. In this scenario the inflaton is displaced from its true vacuum state by some arbitrary mechanism, perhaps quantum or thermal fluctuations. Given this initial state, the inflaton slowly rolls down the potential returning to the true vacuum (see Figure 9). This model has the advantage that no fine-tuning of critical temperature is required. This model presents a scenario, which can be fulfilled by a number of different models.

|

Figure 9. Toy Model For Chaotic Inflation - The inflaton finds itself displaced from the true vacuum and proceeds to `roll' back. Inflation takes place while the inflaton is displaced. |

After the displacement of the inflaton, the universe undergoes inflation as the inflaton rolls back down the potential. Once the inflaton returns to its vacuum (true) state, the universe is reheated by the inflaton coupling to other matter fields. After reheating, the evolution of the universe proceeds in agreement with the Standard Big Bang model.

Although the inflaton could in principle be displaced by a very

large amount, all the inflationist need be concerned with is the

last moments of the evolution. This is when the perturbations in

the scalar field are created that eventually lead to large-scale

structure and anisotropies in the cosmic background. As long as

the inflaton is displaced by a minimal amount (minimal to be

defined in a moment) the initial value problems will be solved.

When considering quantum fluctuations resulting in the

displacement of  , minimal

displacement is easily achieved.

, minimal

displacement is easily achieved.

Successful evolution is only possible if

V( ) is very flat

and has minimal curvature. In terms of (63) and

(64) this suggests that inflation will occur as long as

the SRA requirements hold.

) is very flat

and has minimal curvature. In terms of (63) and

(64) this suggests that inflation will occur as long as

the SRA requirements hold.

This method is successfully used in a number of inflationary models that make predictions in accordance with observation. It must be stated again that Chaotic Inflation results in a very general theory. The inflaton field originally proposed by Guth's model was that of a grand unified theory, but within the Chaotic Inflationary scenario any inflaton field can be used that satisfies the SRA. With these general requirements, potentials used in supergravity, superstrings, and supersymmetry theories can be used to motivate inflation.

Using the energy density obtained in equation (61) one can restate the Friedmann equation (45) in terms of the scalar field.

Also, the equations of motion derived in (55) are restated here for convenience.

Using the SRA, one can simplify these equations by

eliminating the  2 and

2 and

terms. This

leaves the more tractable equations shown below, which remain

valid until

terms. This

leaves the more tractable equations shown below, which remain

valid until  approaches the true

vacuum; i.e.,

approaches the true

vacuum; i.e.,  ~ 1.

~ 1.

where Mp is the Planck mass and has been substituted for G,

remembering that  = c = 1.

= c = 1.

One can use equations (72) and (73) to manifest

the connection between the slow-roll condition (69)

and the generic definition of inflation, that is

> 0.

First note that

> 0.

First note that

For inflation to take place means

(t) > 0 and a(t) is

always positive thus,

(t) > 0 and a(t) is

always positive thus,

Using (72) and differentiating with respect to time,

Plugging this result into (74) gives,

Solving (73) for  and

plugging the result into the last equation, we obtain

and

plugging the result into the last equation, we obtain

Lastly, substituting H2 from (72) one obtains,

But this is just the slow-roll condition

<< 1. So

again one is reminded that inflation will take place until

<< 1. So

again one is reminded that inflation will take place until

~ 1, which has been shown

to be equivalent to

~ 1, which has been shown

to be equivalent to  > 0.

> 0.

25 In much of the literature on

inflation, the slow-roll approximation is presented as a necessary

and sufficient condition for inflation. However, in many new

models of inflation this is not necessary. For a treatment of

these models, see

[43],

[44],

[45, and

references therein]. Back.

26 The

Planck mass is easier to work with opposed to Newton's constant

G, since most of the interesting energy scales are on the order

of GeV (1 eV = 1.6 x 10-19 Joules). In these

units, the Planck mass is  1019 GeV. Back.

1019 GeV. Back.