6.1. The Principle of Self-Regulation

The fossil record in the present-day Universe indicates that every bulged galaxy hosts a supermassive black hole (BH) at its center [206]. This conclusion is derived from a variety of techniques which probe the dynamics of stars and gas in galactic nuclei. The inferred BHs are dormant or faint most of the time, but ocassionally flash in a short burst of radiation that lasts for a small fraction of the Hubble time. The short duty cycle acounts for the fact that bright quasars are much less abundant than their host galaxies, but it begs the more fundamental question: why is the quasar activity so brief? A natural explanation is that quasars are suicidal, namely the energy output from the BHs regulates their own growth.

Supermassive BHs make up a small fraction, < 10-3, of the

total mass

in their host galaxies, and so their direct dynamical impact is limited to

the central star distribution where their gravitational influence

dominates. Dynamical friction on the background stars keeps the BH close to

the center. Random fluctuations in the distribution of stars induces a

Brownian motion of the BH. This motion can be decribed by the same Langevin

equation that captures the motion of a massive dust particle as it responds

to random kicks from the much lighter molecules of air around it

[86].

The characteristic speed by which the BH wanders around the

center is small, ~ (m*

/ MBH)1/2

*, where

m* and MBH are the masses

of a single star and the BH, respectively, and

*, where

m* and MBH are the masses

of a single star and the BH, respectively, and

* is

the stellar velocity dispersion. Since

the random force fluctuates on a dynamical time, the BH wanders across a

region that is smaller by a factor of ~ (m*

/ MBH)1/2 than the region traversed by the

stars inducing the fluctuating force on it.

* is

the stellar velocity dispersion. Since

the random force fluctuates on a dynamical time, the BH wanders across a

region that is smaller by a factor of ~ (m*

/ MBH)1/2 than the region traversed by the

stars inducing the fluctuating force on it.

The dynamical insignificance of the BH on the global galactic scale is

misleading. The gravitational binding energy per rest-mass energy of

galaxies is of order ~

( *

/ c)2 < 10-6. Since BH are

relativistic objects, the gravitational binding energy of material that

feeds them amounts to a substantial fraction its rest mass energy. Even if

the BH mass occupies a fraction as small as ~ 10-4 of the

baryonic

mass in a galaxy, and only a percent of the accreted rest-mass energy leaks

into the gaseous environment of the BH, this slight leakage can unbind the

entire gas reservoir of the host galaxy! This order-of-magnitude estimate

explains why quasars are short lived. As soon as the central BH accretes

large quantities of gas so as to significantly increase its mass, it

releases large amounts of energy that would suppress further accretion onto

it. In short, the BH growth is self-regulated.

*

/ c)2 < 10-6. Since BH are

relativistic objects, the gravitational binding energy of material that

feeds them amounts to a substantial fraction its rest mass energy. Even if

the BH mass occupies a fraction as small as ~ 10-4 of the

baryonic

mass in a galaxy, and only a percent of the accreted rest-mass energy leaks

into the gaseous environment of the BH, this slight leakage can unbind the

entire gas reservoir of the host galaxy! This order-of-magnitude estimate

explains why quasars are short lived. As soon as the central BH accretes

large quantities of gas so as to significantly increase its mass, it

releases large amounts of energy that would suppress further accretion onto

it. In short, the BH growth is self-regulated.

The principle of self-regulation naturally leads to a correlation

between the final BH mass, Mbh, and the depth of the

gravitational

potential well to which the surrounding gas is confined which can be

characterized by the velocity dispersion of the associated stars, ~

*2. Indeed such a correlation

is observed in the present-day Universe

[368].

The observed power-law relation between Mbh

and

*2. Indeed such a correlation

is observed in the present-day Universe

[368].

The observed power-law relation between Mbh

and  *

can be generalized to a correlation between the BH mass

and the circular velocity of the host halo, vc

[130],

which in turn can be related to the halo mass, Mhalo,

and redshift, z

[394]

*

can be generalized to a correlation between the BH mass

and the circular velocity of the host halo, vc

[130],

which in turn can be related to the halo mass, Mhalo,

and redshift, z

[394]

|

(113) |

where

o

o

10-5.7 is

a constant, and as before

10-5.7 is

a constant, and as before

[(

[( m /

m /

mz)(

mz)( c /

18

c /

18 2)],

2)],

mz

mz

[1 + (

[1 + (

/

/

m)(1 +

z)-3]-1,

m)(1 +

z)-3]-1,

c =

18

c =

18 2 + 82d -

39d2, and d =

2 + 82d -

39d2, and d =

mz - 1. If quasars shine near

their Eddington limit as suggested by observations of low and high-redshift

quasars

[134,

384],

then the above value of

mz - 1. If quasars shine near

their Eddington limit as suggested by observations of low and high-redshift

quasars

[134,

384],

then the above value of

o

implies that a fraction of ~ 5 - 10% of the energy released by the

quasar over a galactic dynamical time needs to be captured in the

surrounding galactic gas in order for the BH growth to be self-regulated

[394].

o

implies that a fraction of ~ 5 - 10% of the energy released by the

quasar over a galactic dynamical time needs to be captured in the

surrounding galactic gas in order for the BH growth to be self-regulated

[394].

With this interpretation, the Mbh -

*

relation

reflects the limit introduced to the BH mass by self-regulation; deviations

from this relation are inevitable during episodes of BH growth or as a

result of mergers of galaxies that have no cold gas in them. A physical

scatter around this upper envelope could also result from variations in the

efficiency by which the released BH energy couples to the surrounding gas.

*

relation

reflects the limit introduced to the BH mass by self-regulation; deviations

from this relation are inevitable during episodes of BH growth or as a

result of mergers of galaxies that have no cold gas in them. A physical

scatter around this upper envelope could also result from variations in the

efficiency by which the released BH energy couples to the surrounding gas.

Various prescriptions for self-regulation were sketched by Silk & Rees

[339].

These involve either energy or momentum-driven winds, where

the latter type is a factor of ~ vc / c less

efficient

[35,

199,

262].

Wyithe & Loeb

[394]

demonstrated that a

particularly simple prescription for an energy-driven wind can reproduce

the luminosity function of quasars out to highest measured redshift,

z ~ 6 (see Figs. 38 and

40), as well as the observed

clustering properties of quasars at z ~ 3

[398]

(see Fig. 41). The prescription postulates

that: (i)

self-regulation leads to the growth of Mbh up the

redshift-independent limit as a function of vc in

Eq. (113), for

all galaxies throughout their evolution; and (ii) the growth of

Mbh to the limiting mass in Eq. (113) occurs through halo

merger episodes during which the BH shines at its Eddington luminosity

(with the median quasar spectrum) over the dynamical time of its host

galaxy, tdyn. This model has only one adjustable

parameter, namely the fraction of the released quasar energy that

couples to the surrounding gas in the host galaxy. This parameter can be

fixed based on the Mbh -

*

relation in the local Universe

[130].

It is remarkable that the combination of the above simple

prescription and the standard

*

relation in the local Universe

[130].

It is remarkable that the combination of the above simple

prescription and the standard

CDM cosmology for

the evolution and

merger rate of galaxy halos, lead to a satisfactory agreement with the rich

data set on quasar evolution over cosmic history.

CDM cosmology for

the evolution and

merger rate of galaxy halos, lead to a satisfactory agreement with the rich

data set on quasar evolution over cosmic history.

|

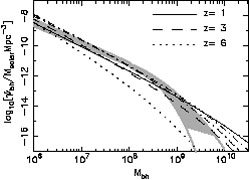

Figure 38. Comparison of the observed and

model luminosity functions (from

[394]).

The data points at z < 4 are summarized in Ref.

[286],

while the light lines show the double power-law fit to the 2dF

quasar luminosity function

[56].

At z ~ 4.3 and z ~ 6.0 the data is from Refs.

[125].

The grey regions show the 1 - |

|

Figure 39. Simulation images of a merger of galaxies resulting in quasar activity that eventually shuts-off the accretion of gas onto the black hole (from Di Matteo et al. 2005 [108]). The upper (lower) panels show a sequence of snapshots of the gas distribution during a merger with (without) feedback from a central black hole. The temperature of the gas is color coded. |

|

Figure 40. The comoving density of supermassive BHs per unit BH mass (from [394]). The grey region shows the estimate based on the observed velocity distribution function of galaxies in Ref. [336] and the Mbh - vc relation in Eq. (113). The lower bound corresponds to the lower limit in density for the observed velocity function while the grey lines show the extrapolation to lower densities. We also show the mass function computed at z = 1, 3 and 6 from the Press-Schechter [292] halo mass function and Eq. (113), as well as the mass function at z ~ 2.35 and z ~ 3 implied by the observed density of quasars and a quasar lifetime of order the dynamical time of the host galactic disk, tdyn (dot-dashed lines). |

|

Figure 41. Predicted correlation function

of quasars at various redshifts in comparison to the 2dF data

[101]

(from

[398]).

The dark lines show the correlation function predictions for quasars of

various apparent B-band magnitudes. The 2dF limit is

B ~ 20.85. The lower

right panel shows data from entire 2dF sample in comparison to the

theoretical prediction at the mean quasar redshift of

<z> = 1.5. The B = 20.85 prediction at this redshift

is also shown by

thick gray lines in the other panels to guide the eye. The predictions are

based on the scaling Mbh

|

The cooling time of the heated gas is typically longer than its dynamical time and so the gas should expand into the galactic halo and escape the galaxy if its initial temperature exceeds the virial temperature of the galaxy [394]. The quasar remains active during the dynamical time of the initial gas reservoir, ~ 107 years, and fades afterwards due to the dilution of this reservoir. Accretion is halted as soon as the quasar supplies the galactic gas with more than its binding energy. The BH growth may resume if the cold gas reservoir is replenished through a new merger.

Following the early analytic work, extensive numerical simulations by Springel, Hernquist, & Di Matteo (2005) [350] (see also Di Matteo et al. 2005 [108]) demonstrated that galaxy mergers do produce the observed correlations between black hole mass and spheroid properties when a similar energy feedback is incorporated. Because of the limited resolution near the galaxy nucleus, these simulations adopt a simple prescription for the accretion flow that feeds the black hole. The actual feedback in reality may depend crucially on the geometry of this flow and the physical mechanism that couples the energy or momentum output of the quasar to the surrounding gas.

Agreement between the predicted and observed correlation function of quasars (Fig. 41) is obtained only if the BH mass scales with redshift as in Eq. (113) and the quasar lifetime is of the order of the dynamical time of the host galactic disk [398],

|

(114) |

This characterizes the timescale it takes low angular momentum gas to settle inwards and feed the black hole from across the galaxy before feedback sets in and suppresses additional infall. It also characterizes the timescale for establishing an outflow at the escape speed from the host spheroid.

The inflow of cold gas towards galaxy centers during the growth phase of

the BH would naturally be accompanied by a burst of star formation. The

fraction of gas that is not consumed by stars or ejected by supernovae,

will continue to feed the BH. It is therefore not surprising that quasar

and starburst activities co-exist in Ultra Luminous Infrared Galaxies

[356],

and that all quasars show broad metal lines indicating a

super-solar metallicity of the surrounding gas

[106].

Applying a

similar self-regulation principle to the stars, leads to the expectation

[394,

197]

that the ratio between the mass of the BH and the mass in

stars is independent of halo mass (as observed locally

[243])

but increases with redshift as

(z)1/2(1 +

z)3/2. A

consistent trend has indeed been inferred in an observed sample of

gravitationally-lensed quasars

[305].

(z)1/2(1 +

z)3/2. A

consistent trend has indeed been inferred in an observed sample of

gravitationally-lensed quasars

[305].

The upper mass of galaxies may also be regulated by the energy output from

quasar activity. This would account for the fact that cooling flows are

suppressed in present-day X-ray clusters

[123,

91,

273], and that

massive BHs and stars in galactic bulges were already formed at z ~

2. The quasars discovered by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey

(SDSS) at z ~ 6 mark the early growth of the most massive

BHs and galactic spheroids. The present-day abundance of galaxies capable of

hosting BHs of mass ~ 109

M (based

on Eq. 113) already existed at z ~ 6

[225].

At some epoch, the quasar energy output

may have led to the extinction of cold gas in these galaxies and the

suppression of further star formation in them, leading to an apparent

"anti-hierarchical" mode of galaxy formation where massive spheroids

formed early and did not make new stars at late times. In the course of

subsequent merger events, the cores of the most massive spheroids acquired

an envelope of collisionless matter in the form of already-formed stars or

dark matter

[225],

without the proportional accretion of cold gas

into the central BH. The upper limit on the mass of the central BH and the

mass of the spheroid is caused by the lack of cold gas and cooling flows in

their X-ray halos. In the cores of cooling X-ray clusters, there is often

an active central BH that supplies sufficient energy to compensate for the

cooling of the gas

[91,

123,

35].

The primary physical process

by which this energy couples to the gas is still unknown.

(based

on Eq. 113) already existed at z ~ 6

[225].

At some epoch, the quasar energy output

may have led to the extinction of cold gas in these galaxies and the

suppression of further star formation in them, leading to an apparent

"anti-hierarchical" mode of galaxy formation where massive spheroids

formed early and did not make new stars at late times. In the course of

subsequent merger events, the cores of the most massive spheroids acquired

an envelope of collisionless matter in the form of already-formed stars or

dark matter

[225],

without the proportional accretion of cold gas

into the central BH. The upper limit on the mass of the central BH and the

mass of the spheroid is caused by the lack of cold gas and cooling flows in

their X-ray halos. In the cores of cooling X-ray clusters, there is often

an active central BH that supplies sufficient energy to compensate for the

cooling of the gas

[91,

123,

35].

The primary physical process

by which this energy couples to the gas is still unknown.

6.2. Feedback on Large Intergalactic Scales

Aside from affecting their host galaxy, quasars disturb their large-scale

cosmological environment. Powerful quasar outflows are observed in the form

of radio jets

[34]

or broad-absorption-line winds

[160].

The amount of energy carried by these outflows is largely

unknown, but could be comparable to the radiative output from the same

quasars. Furlanetto & Loeb

[139]

have calculated the intergalactic

volume filled by such outflows as a function of cosmic time (see

Fig. 42). This volume is likely to contain

magnetic fields and

metals, providing a natural source for the observed magnetization of the

metal-rich gas in X-ray clusters

[207]

and in galaxies

[103].

The injection of energy by quasar outflows may also explain the deficit of

Ly absorption in the

vicinity of Lyman-break galaxies

[7,

100]

and the required pre-heating in X-ray clusters

[54,

91].

absorption in the

vicinity of Lyman-break galaxies

[7,

100]

and the required pre-heating in X-ray clusters

[54,

91].

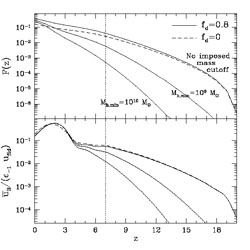

|

Figure 42. The global influence of

magnetized quasar outflows on the intergalactic medium (from

[139]).

Upper Panel: Predicted

volume filling fraction of magnetized quasar bubbles

F(z), as a function

of redshift. Lower Panel: Ratio of normalized magnetic energy

density, |

Beyond the reach of their outflows, the brightest SDSS quasars at

z > 6 are inferred to have ionized exceedingly large regions

of gas (tens of comoving Mpc) around them prior to global reionization (see

Fig. 43 and Refs.

[381,

400]).

Thus, quasars must have

suppressed the faint-end of the galaxy luminosity function in these regions

before the same occurred throughout the Universe. The recombination time

is comparable to the Hubble time for the mean gas density at z ~

7 and so ionized regions persist

[272]

on these large scales where

inhomogeneities are small. The minimum galaxy mass is increased by at

least an order of magnitude to a virial temperature of ~ 105

K in these ionized regions

[23].

It would be particularly interesting to examine whether the faint end

( *

< 30 km s-1) of

the luminosity function of dwarf galaxies shows any moduluation on

large-scales around rare massive BHs, such as M87.

*

< 30 km s-1) of

the luminosity function of dwarf galaxies shows any moduluation on

large-scales around rare massive BHs, such as M87.

|

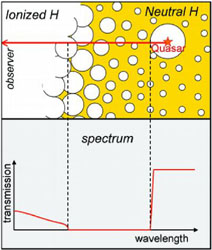

Figure 43. Quasars serve as probes of the

end of reionization. The measured

size of the HII regions around SDSS quasars can be used

[396,

251]

to demonstrate that a significant fraction of the

intergalactic hydrogen was neutral at z ~ 6.3 or else the

inferred size of the quasar HII regions would have been much larger

than observed (assuming typical quasar lifetimes

[248]).

Also, quasars can be

used to measure the redshift at which the intergalactic medium started to

transmit Ly |

To find the volume filling fraction of relic regions from z ~ 6, we

consider a BH of mass Mbh ~ 3 × 109

M . We

can estimate

the comoving density of BHs directly from the observed quasar luminosity

function and our estimate of quasar lifetime. At z ~ 6, quasars

powered by Mbh ~ 3 × 109

M

. We

can estimate

the comoving density of BHs directly from the observed quasar luminosity

function and our estimate of quasar lifetime. At z ~ 6, quasars

powered by Mbh ~ 3 × 109

M BHs

had a comoving density of ~ 0.5G pc-3

[394].

However, the Hubble time exceeds

tdyn by a factor of ~ 2 × 102

(reflecting the square

root of the density contrast of cores of galaxies relative to the mean

density of the Universe), so that the comoving density of the bubbles

created by the z ~ 6 BHs is ~ 102Gpc-3 (see

Fig. 40). The density implies that the volume

filling fraction of relic z ~ 6 regions is small, < 10%, and

that the nearest BH that had Mbh ~ 3 × 109

M

BHs

had a comoving density of ~ 0.5G pc-3

[394].

However, the Hubble time exceeds

tdyn by a factor of ~ 2 × 102

(reflecting the square

root of the density contrast of cores of galaxies relative to the mean

density of the Universe), so that the comoving density of the bubbles

created by the z ~ 6 BHs is ~ 102Gpc-3 (see

Fig. 40). The density implies that the volume

filling fraction of relic z ~ 6 regions is small, < 10%, and

that the nearest BH that had Mbh ~ 3 × 109

M at

z ~ 6 (and could have been

detected as an SDSS quasar then) should be at a distance

dbh ~ (4

at

z ~ 6 (and could have been

detected as an SDSS quasar then) should be at a distance

dbh ~ (4 / 3 × 102)1/3 Gpc ~ 140 Mpc

which is almost an order-of-magnitude larger than the distance of M87, a

galaxy known to possess a BH of this mass

[135].

/ 3 × 102)1/3 Gpc ~ 140 Mpc

which is almost an order-of-magnitude larger than the distance of M87, a

galaxy known to possess a BH of this mass

[135].

What is the most massive BH that can be detected dynamically in a

local galaxy redshift survey? SDSS probes a volume of

~ 1 Gpc3 out to a distance ~ 30 times that of M87. At the

peak of quasar activity at z ~ 3, the density of the brightest

quasars implies that there should be ~ 100 BHs with masses of

3 × 1010

M per

Gpc3, the nearest of which will be

at a distance dbh ~ 130 Mpc, or ~ 7 times the distance

to M87. The radius of gravitational influence of the BH scales as

Mbh / vc2

per

Gpc3, the nearest of which will be

at a distance dbh ~ 130 Mpc, or ~ 7 times the distance

to M87. The radius of gravitational influence of the BH scales as

Mbh / vc2

Mbh3/5. We find that for the nearest

3 × 109

M

Mbh3/5. We find that for the nearest

3 × 109

M and 3

× 1010

M

and 3

× 1010

M BHs,

the angular radius of

influence should be similar. Thus, the dynamical signature of ~

3 × 1010

M

BHs,

the angular radius of

influence should be similar. Thus, the dynamical signature of ~

3 × 1010

M BHs on

their stellar host should be detectable.

BHs on

their stellar host should be detectable.

6.3. What seeded the growth of the supermassive black holes?

The BHs powering the bright SDSS quasars possess a mass of a few

× 109

M , and

reside in galaxies with a velocity dispersion of ~ 500 km s-1

[24].

A quasar radiating at its

Eddington limiting luminosity, Le = 1.4 ×

1046 erg s-1(Mbh / 108

M

, and

reside in galaxies with a velocity dispersion of ~ 500 km s-1

[24].

A quasar radiating at its

Eddington limiting luminosity, Le = 1.4 ×

1046 erg s-1(Mbh / 108

M ), with

a radiative efficiency,

), with

a radiative efficiency,

rad =

Le /

rad =

Le /  c2 would grow exponentially in mass as

a function of time t, Mbh =

Mseed exp{t / te} on a time

scale, te = 4.1 × 107 yr

(

c2 would grow exponentially in mass as

a function of time t, Mbh =

Mseed exp{t / te} on a time

scale, te = 4.1 × 107 yr

( rad /

0.1). Thus, the required growth time in units of the Hubble time

thubble = 9 ×

108 yr[(1 + z) / 7]-3/2 is

rad /

0.1). Thus, the required growth time in units of the Hubble time

thubble = 9 ×

108 yr[(1 + z) / 7]-3/2 is

|

(115) |

The age of the Universe at z ~ 6 provides just sufficient time to

grow an SDSS BH with Mbh ~ 109

M out of

a stellar mass seed with

out of

a stellar mass seed with

rad = 10%

[175].

The growth time is

shorter for smaller radiative efficiencies, as expected if the seed

originates from the optically-thick collapse of a supermassive star (in

which case Mseed in the logarithmic factor is also

larger).

rad = 10%

[175].

The growth time is

shorter for smaller radiative efficiencies, as expected if the seed

originates from the optically-thick collapse of a supermassive star (in

which case Mseed in the logarithmic factor is also

larger).

What was the mass of the initial BH seeds? Were they planted in early

dwarf galaxies through the collapse of massive, metal free (Pop-III) stars

(leading to Mseed of hundreds of solar masses)

or through the collapse of even more massive, i.e. supermassive, stars

[220] ?

Bromm & Loeb

[63]

have shown through a hydrodynamical simulation

(see Fig. 44) that supermassive stars were

likely to form in early

galaxies at z ~ 10 in which the virial temperature was close to the

cooling threshold of atomic hydrogen, ~ 104 K. The gas in these

galaxies condensed into massive ~ 106

M clumps

(the progenitors

of supermassive stars), rather than fragmenting into many small clumps (the

progenitors of stars), as it does in environments that are much hotter than

the cooling threshold. This formation channel requires that a galaxy be

close to its cooling threshold and immersed in a UV background that

dissociates molecular hydrogen in it. These requirements should make this

channel sufficiently rare, so as not to overproduce the cosmic mass density

of supermassive BH.

clumps

(the progenitors

of supermassive stars), rather than fragmenting into many small clumps (the

progenitors of stars), as it does in environments that are much hotter than

the cooling threshold. This formation channel requires that a galaxy be

close to its cooling threshold and immersed in a UV background that

dissociates molecular hydrogen in it. These requirements should make this

channel sufficiently rare, so as not to overproduce the cosmic mass density

of supermassive BH.

|

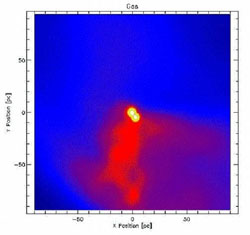

Figure 44. SPH simulation of the collapse

of an early dwarf galaxy with a

virial temperature just above the cooling threshold of atomic hydrogen and

no H2 (from

[63]).

The image shows a snapshot of the gas density distribution at z

|

The minimum seed BH mass can be identified observationally through the detection of gravitational waves from BH binaries with Advanced LIGO [395] or with LISA [393]. Most of the mHz binary coalescence events originate at z > 7 if the earliest galaxies included BHs that obey the Mbh - vc relation in Eq. (113). The number of LISA sources per unit redshift per year should drop substantially after reionization, when the minimum mass of galaxies increased due to photo-ionization heating of the intergalactic medium. Studies of the highest redshift sources among the few hundred detectable events per year, will provide unique information about the physics and history of BH growth in galaxies [327].

The early BH progenitors can also be detected as unresolved point sources, using the future James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Unfortunately, the spectrum of metal-free massive and supermassive stars is the same, since their surface temperature ~ 105 K is independent of mass [59]. Hence, an unresolved cluster of massive early stars would show the same spectrum as a supermassive star of the same total mass.

It is difficult to ignore the possible environmental impact of

quasars on anthropic selection. One may wonder whether it is not a

coincidence that our Milky-Way Galaxy has a relatively modest BH mass of

only a few million solar masses in that the energy output from a much more

massive (e.g. ~ 109

M ) black

hole would have disrupted the evolution of life on our planet. A proper

calculation remains to be done (as in the context of nearby Gamma-Ray Bursts

[316])

in order to demonstrate any such link.

) black

hole would have disrupted the evolution of life on our planet. A proper

calculation remains to be done (as in the context of nearby Gamma-Ray Bursts

[316])

in order to demonstrate any such link.