In this section, we provide a brief review of the elements of the FRW cosmological model. This model provides the context for interpreting the observational evidence for cosmic acceleration as well as the framework for understanding how cosmological probes in the future will help uncover the cause of acceleration by determining the history of the cosmic expansion with greater precision. For further details on basic cosmology, see, e.g., the textbooks of [Dodelson 2003, Kolb & Turner 1990, Peacock 1999], and [Peebles 1993]. Note that we follow the standard practice of using units in which the speed of light c = 1.

2.1. Friedmann-Robertson-Walker cosmology

From the large-scale distribution of galaxies and the near-uniformity of the CMB temperature, we have good evidence that the Universe is nearly homogeneous and isotropic. Under this assumption, the spacetime metric can be written in the FRW form,

|

(1) |

where r,

,

,

are comoving spatial

coordinates, t is time, and

the expansion is described by the cosmic scale factor,

a(t) (by convention, a = 1 today). The quantity

k is the curvature of 3-dimensional space: k = 0

corresponds to a spatially flat, Euclidean Universe, k > 0 to

positive curvature (3-sphere), and k < 0 to negative curvature

(saddle).

are comoving spatial

coordinates, t is time, and

the expansion is described by the cosmic scale factor,

a(t) (by convention, a = 1 today). The quantity

k is the curvature of 3-dimensional space: k = 0

corresponds to a spatially flat, Euclidean Universe, k > 0 to

positive curvature (3-sphere), and k < 0 to negative curvature

(saddle).

The wavelengths  of

photons moving through the Universe scale

with a(t), and the redshift of light emitted from a

distant source at time tem, 1 + z =

of

photons moving through the Universe scale

with a(t), and the redshift of light emitted from a

distant source at time tem, 1 + z =

obs /

obs /

em

=1/a(tem), directly reveals the relative

size of the Universe at that time. This means that time intervals are

related to redshift intervals by dt =

-dz / H(z)(1 + z), where H

em

=1/a(tem), directly reveals the relative

size of the Universe at that time. This means that time intervals are

related to redshift intervals by dt =

-dz / H(z)(1 + z), where H

/ a is the

Hubble parameter, and an overdot denotes a time

derivative. The present value of the Hubble parameter is conventionally

expressed as H0 = 100 h km/sec/Mpc, where

h

/ a is the

Hubble parameter, and an overdot denotes a time

derivative. The present value of the Hubble parameter is conventionally

expressed as H0 = 100 h km/sec/Mpc, where

h  0.7 is the

dimensionless Hubble parameter. Here and below, a subscript "0" on a

parameter denotes its value at the present epoch.

0.7 is the

dimensionless Hubble parameter. Here and below, a subscript "0" on a

parameter denotes its value at the present epoch.

The key equations of cosmology are the Friedmann equations, the field equations of GR applied to the FRW metric,

|

(2)

|

where  is the

total energy

density of the Universe (sum of matter, radiation, dark energy), and

p is the total pressure (sum of pressures of each component). For

historical reasons we display the cosmological constant

is the

total energy

density of the Universe (sum of matter, radiation, dark energy), and

p is the total pressure (sum of pressures of each component). For

historical reasons we display the cosmological constant

here;

hereafter, we shall always represent it as vacuum energy and subsume it

into the density and pressure terms; the correspondence is:

here;

hereafter, we shall always represent it as vacuum energy and subsume it

into the density and pressure terms; the correspondence is:

=

8

=

8 G

G

VAC

= -8

VAC

= -8 G

pVAC.

G

pVAC.

For each component, the conservation of energy is expressed by

d(a3

i ) =

-pi da3, the expanding

Universe analogue of the first law of thermodynamics,

dE = -pdV. Thus, the evolution of energy density is

controlled by the ratio of the pressure to the energy density, the

equation-of-state parameter, wi

i ) =

-pi da3, the expanding

Universe analogue of the first law of thermodynamics,

dE = -pdV. Thus, the evolution of energy density is

controlled by the ratio of the pressure to the energy density, the

equation-of-state parameter, wi

pi

/

pi

/  i.

1 For the general case,

this ratio varies with time, and the evolution of the energy density in

a given component is given by

i.

1 For the general case,

this ratio varies with time, and the evolution of the energy density in

a given component is given by

|

(4) |

In the case of constant wi,

|

(5) |

For non-relativistic matter, which includes both dark matter and

baryons, wM = 0 to very good approximation, and

M

M

(1 +

z)3; for radiation, i.e., relativistic particles,

wR = 1/3, and

(1 +

z)3; for radiation, i.e., relativistic particles,

wR = 1/3, and

R

R

(1 +

z)4. For vacuum energy, as noted above

pVAC =

-

(1 +

z)4. For vacuum energy, as noted above

pVAC =

- VAC

= -

VAC

= - /

8

/

8 G = constant, i.e.,

wVAC = -1. For other models of dark energy, w

can differ from -1 and vary in time.

[Hereafter, w without a subscript refers to dark energy.]

G = constant, i.e.,

wVAC = -1. For other models of dark energy, w

can differ from -1 and vary in time.

[Hereafter, w without a subscript refers to dark energy.]

The present energy density of a flat Universe (k = 0),

crit

crit

3H02 /

8

3H02 /

8 G = 1.88 ×

10-29 h2 gm

cm-3 = 8.10 × 10-47

h2 GeV4, is known as the critical density;

it provides a convenient means of normalizing cosmic energy densities,

where

G = 1.88 ×

10-29 h2 gm

cm-3 = 8.10 × 10-47

h2 GeV4, is known as the critical density;

it provides a convenient means of normalizing cosmic energy densities,

where  i =

i =

i(t0) /

i(t0) /

crit.

For a positively curved Universe,

crit.

For a positively curved Universe,

0

0

(t0)

/

(t0)

/ crit

> 1 and for a negatively curved Universe

crit

> 1 and for a negatively curved Universe

0 <

1. The present value of the curvature radius, Rcurv

0 <

1. The present value of the curvature radius, Rcurv

a

/ (|k|)1/2, is related to

a

/ (|k|)1/2, is related to

0 and

H0 by Rcurv =

H0-1 /

(|

0 and

H0 by Rcurv =

H0-1 /

(| 0

- 1|)1/2, and the

characteristic scale H0-1

0

- 1|)1/2, and the

characteristic scale H0-1

3000 h-1 Mpc is known as the Hubble radius.

Because of the evidence from the CMB that the Universe is nearly

spatially flat (see Fig. 8), we shall assume k = 0 except where

otherwise noted.

3000 h-1 Mpc is known as the Hubble radius.

Because of the evidence from the CMB that the Universe is nearly

spatially flat (see Fig. 8), we shall assume k = 0 except where

otherwise noted.

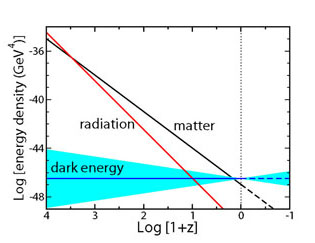

Fig. 1

shows the evolution of the radiation, matter, and dark energy densities

with redshift. The Universe has gone through three distinct eras:

radiation-dominated, z

3000;

matter-dominated, 3000

3000;

matter-dominated, 3000

z

z

0.5; and

dark-energy dominated, z

0.5; and

dark-energy dominated, z

0.5. The

evolution of the scale factor is controlled by the

dominant energy form: a(t)

0.5. The

evolution of the scale factor is controlled by the

dominant energy form: a(t)

t2/3(1 + w) (for constant w). During the

radiation-dominated era, a(t)

t2/3(1 + w) (for constant w). During the

radiation-dominated era, a(t)

t1/2; during the matter-dominated era,

a(t)

t1/2; during the matter-dominated era,

a(t)  t2/3; and for the dark

energy-dominated era, assuming w = -1, asymptotically

a(t)

t2/3; and for the dark

energy-dominated era, assuming w = -1, asymptotically

a(t)  exp(Ht). For a flat Universe with

matter and vacuum energy, the general solution, which approaches the

latter two above at early and late times, is a(t)

= (

exp(Ht). For a flat Universe with

matter and vacuum energy, the general solution, which approaches the

latter two above at early and late times, is a(t)

= ( M

/

M

/  VAC)1/3

(sinh[3(

VAC)1/3

(sinh[3( VAC)1/2

H0 t / 2])2/3.

VAC)1/2

H0 t / 2])2/3.

|

Figure 1. Evolution of radiation, matter, and dark energy densities with redshift. For dark energy, the band represents w = -1 ± 0.2. |

The deceleration parameter, q(z), is defined as

|

(6) |

where

i(z)

i(z)

i(z) /

i(z) /

crit(z)

is the fraction of critical density in component i at redshift

z. During the matter- and radiation-dominated eras,

wi > 0 and gravity slows the expansion, so

that q > 0 and

crit(z)

is the fraction of critical density in component i at redshift

z. During the matter- and radiation-dominated eras,

wi > 0 and gravity slows the expansion, so

that q > 0 and

< 0. Because of the

(

< 0. Because of the

( +

3p) term in the second Friedmann equation (Newtonian cosmology

would only have

+

3p) term in the second Friedmann equation (Newtonian cosmology

would only have

), the gravity

of a component that satisfies p <

-

), the gravity

of a component that satisfies p <

- / 3, i.e.,

w < -1/3, is repulsive and can cause the expansion to accelerate

(

/ 3, i.e.,

w < -1/3, is repulsive and can cause the expansion to accelerate

( > 0): we take this

to be the defining property of dark energy. The successful predictions

of the radiation-dominated era of cosmology, e.g., big bang

nucleosynthesis and the formation of CMB anisotropies, provide evidence

for the (

> 0): we take this

to be the defining property of dark energy. The successful predictions

of the radiation-dominated era of cosmology, e.g., big bang

nucleosynthesis and the formation of CMB anisotropies, provide evidence

for the ( +

3p) term, since during this epoch

+

3p) term, since during this epoch

is

about twice as large as it would be in Newtonian cosmology.

is

about twice as large as it would be in Newtonian cosmology.

2.2. Distances and the Hubble diagram

For an object of intrinsic luminosity L, the measured energy flux F defines the luminosity distance dL to the object, i.e., the distance inferred from the inverse square law. The luminosity distance is related to the cosmological model through

|

(7) |

where r(z) is the comoving distance to an object at redshift z,

|

(8)

|

and where

(x) =

sin(x) for k > 0 and

sinh(x) for k < 0. Specializing to the flat model and

constant w,

(x) =

sin(x) for k > 0 and

sinh(x) for k < 0. Specializing to the flat model and

constant w,

|

(10) |

where  M

is the present fraction of critical

density in non-relativistic matter, and

M

is the present fraction of critical

density in non-relativistic matter, and

R

R

0.8 ×

10-4 represents the small contribution to

the present energy density from photons and relativistic neutrinos. In

this model, the dependence of cosmic distances upon dark energy is

controlled by the parameters

0.8 ×

10-4 represents the small contribution to

the present energy density from photons and relativistic neutrinos. In

this model, the dependence of cosmic distances upon dark energy is

controlled by the parameters

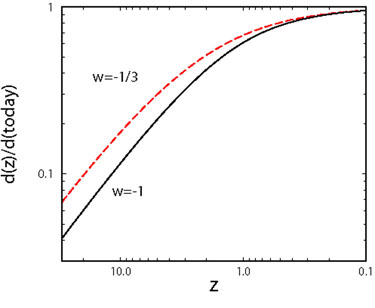

M and

w and

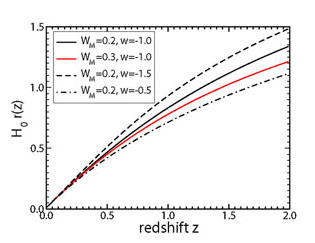

is shown in the left panel of Fig. 2.

M and

w and

is shown in the left panel of Fig. 2.

|

|

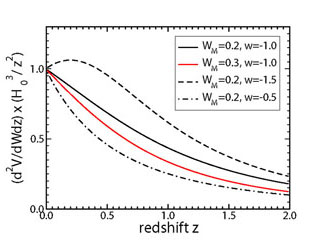

Figure 2. For a flat Universe,

the effect of dark energy upon cosmic distance (left) and volume element

(right) is controlled by

|

|

The luminosity distance is related to the distance modulus µ by

|

(11) |

where m is the apparent magnitude of the object (proportional to the log of the flux) and M is the the absolute magnitude (proportional to the log of the intrinsic luminosity). "Standard candles," objects of fixed absolute magnitude M, and measurements of the logarithmic energy flux m constrain the cosmological model and thereby the expansion history through this magnitude-redshift relation, known as the Hubble diagram.

Expanding the scale factor around its value today, a(t) = 1 + H0 (t - t0) - q0 H02 (t - t0)2 / 2 + ··· , the distance-redshift relation can be written in its historical form

|

(12) |

The expansion rate and deceleration rate today appear in the first two terms in the Taylor expansion of the relation. This expansion, only valid for z << 1, is of historical significance and utility; it is not useful today since objects as distant as redshift z ~ 2 are being used to probe the expansion history. However, it does illustrate the general principle: the first term on the r.h.s. represents the linear Hubble expansion, and the deviation from a linear relation reveals the deceleration (or acceleration).

The angular-diameter distance dA, the distance

inferred from the angular size

of a distant object of

fixed diameter D, is defined by dA

of a distant object of

fixed diameter D, is defined by dA

D /

D /

=

r(z) / (1 + z) = dL /

(1 + z)2. The

use of "standard rulers" (objects of fixed intrinsic size)

provides another means of probing the expansion history, again through

r(z).

=

r(z) / (1 + z) = dL /

(1 + z)2. The

use of "standard rulers" (objects of fixed intrinsic size)

provides another means of probing the expansion history, again through

r(z).

The cosmological time, or time back to the Big Bang, is given by

|

(13) |

While the present age in principle depends upon the expansion rate at

very early times, the rapid rise of H(z) with z

— a factor of 30,000 between today and the epoch of last

scattering, when photons and baryons decoupled, at

zLS  1100,

t(zLS)

1100,

t(zLS)

380,000 years —

makes this point moot.

380,000 years —

makes this point moot.

Finally, the comoving volume element per unit solid angle

d is given by

is given by

|

(14) |

For a set of objects of known comoving density n(z), the

comoving volume element can be used to infer

r2(z) / H(z) from the number counts

per unit redshift and solid angle, d2 N /

dzd =

n(z) d2 V /

dzd

=

n(z) d2 V /

dzd . The

dependence of the comoving volume element upon

. The

dependence of the comoving volume element upon

M and

w is shown in the right panel of Fig. 2.

M and

w is shown in the right panel of Fig. 2.

2.3. Growth of structure and

CDM

CDM

A striking success of the consensus cosmology

is its ability to account for the observed structure in the Universe,

provided that the dark matter is composed of slowly moving particles,

known as cold dark matter (CDM), and that the initial power spectrum of

density perturbations is nearly scale-invariant, P(k)

~ knS with spectral index

nS  1,

as predicted by inflation

[Springel, Frenk

& White 2006].

Dark energy affects the development of structure by

its influence on the expansion rate of the Universe when density

perturbations are growing. This fact and the quantity and quality of

large-scale structure data make structure formation a sensitive probe of

dark energy.

1,

as predicted by inflation

[Springel, Frenk

& White 2006].

Dark energy affects the development of structure by

its influence on the expansion rate of the Universe when density

perturbations are growing. This fact and the quantity and quality of

large-scale structure data make structure formation a sensitive probe of

dark energy.

In GR the growth of small-amplitude, matter-density perturbations on length scales much smaller than the Hubble radius is governed by

|

(15) |

where the perturbations

(x, t)

(x, t)

M(x, t)

/

M(x, t)

/  M(t) have been decomposed into their

Fourier modes of wavenumber k, and matter is assumed to be

pressureless (always true for the CDM portion and valid for the baryons

on mass scales larger than 105

M

M(t) have been decomposed into their

Fourier modes of wavenumber k, and matter is assumed to be

pressureless (always true for the CDM portion and valid for the baryons

on mass scales larger than 105

M after

photon-baryon

decoupling). Dark energy affects the growth through the "Hubble

damping" term,

2H

after

photon-baryon

decoupling). Dark energy affects the growth through the "Hubble

damping" term,

2H k.

k.

The solution to Eq. (15) is simple to describe during the

three epochs of expansion discussed earlier:

k

(t) grows as a(t) during the matter-dominated epoch

and is approximately constant during the radiation-dominated and dark

energy-dominated epochs. The key feature here is the fact that once

accelerated expansion begins, the growth of linear perturbations

effectively ends, since the Hubble damping time becomes shorter than the

timescale for perturbation growth.

k

(t) grows as a(t) during the matter-dominated epoch

and is approximately constant during the radiation-dominated and dark

energy-dominated epochs. The key feature here is the fact that once

accelerated expansion begins, the growth of linear perturbations

effectively ends, since the Hubble damping time becomes shorter than the

timescale for perturbation growth.

The impact of the dark energy equation-of-state parameter w on

the growth of structure is more subtle and is illustrated in

Fig. 3. For larger w and fixed

dark energy density

DE, dark

energy comes to

dominate earlier, causing the growth of linear perturbations to end

earlier; this means the growth factor since decoupling is smaller and

that to achieve the same amplitude by today, the perturbation must begin

with larger amplitude and is larger at all redshifts until today. The

same is true for larger

DE, dark

energy comes to

dominate earlier, causing the growth of linear perturbations to end

earlier; this means the growth factor since decoupling is smaller and

that to achieve the same amplitude by today, the perturbation must begin

with larger amplitude and is larger at all redshifts until today. The

same is true for larger

DE and fixed

w. Finally, if dark energy is dynamical (not vacuum energy), then

in principle it can be inhomogeneous, an effect ignored above. In

practice, it is expected to be nearly uniform over scales smaller than

the present Hubble radius, in sharp contrast to dark matter, which can

clump on small scales.

DE and fixed

w. Finally, if dark energy is dynamical (not vacuum energy), then

in principle it can be inhomogeneous, an effect ignored above. In

practice, it is expected to be nearly uniform over scales smaller than

the present Hubble radius, in sharp contrast to dark matter, which can

clump on small scales.

|

Figure 3. Growth of linear density

perturbations in a flat universe with dark energy. Note that the

growth of perturbations ceases when dark energy begins to dominate, 1 +

z =

( |

1 A perfect fluid is fully characterized

by its isotropic pressure p and energy density

, where

p is a function of density and other state variables (e.g.,

temperature). The equation-of-state parameter w = p /

, where

p is a function of density and other state variables (e.g.,

temperature). The equation-of-state parameter w = p /

determines the

evolution of the energy density

determines the

evolution of the energy density

; e.g.,

; e.g.,

V1 +

w for constant w, where V is the volume

occupied by the fluid. Vacuum energy or a homogeneous scalar field are

spatially uniform and they too can be fully characterized by

w. The evolution of an inhomogeneous, imperfect fluid is in

general complicated and not fully described by w. Nonetheless, in

the FRW cosmology, spatial homogeneity and isotropy require the

stress-energy to take the perfect fluid form; thus,

w determines the evolution of the energy density.

Back.

V1 +

w for constant w, where V is the volume

occupied by the fluid. Vacuum energy or a homogeneous scalar field are

spatially uniform and they too can be fully characterized by

w. The evolution of an inhomogeneous, imperfect fluid is in

general complicated and not fully described by w. Nonetheless, in

the FRW cosmology, spatial homogeneity and isotropy require the

stress-energy to take the perfect fluid form; thus,

w determines the evolution of the energy density.

Back.