3.2. Results and notes on selected galaxies

In this subsection a brief description of the observed eDIG morphology

of selected galaxies is presented in addition to some background

information, relevant in the DIG context for those targets. The galaxies

are listed according to their increasing Right Ascension. The

H images

of all survey galaxies are shown together with the accompanying broad band

images (R-band, and unsharp-masked R-band image) in Figs. 22-54

(available only in electronic form at EDP Sciences). However, some

enlargements of selected galaxies with characteristic and spectacular

eDIG morphology are included in logarithmic scale as separate figures in

this section, in order to highlight some finer details of eDIG emission. A

comparison with observations by other researchers from various wavelength

regimes in the context of the disk-halo interaction is made, whenever such

observations were available in the literature.

images

of all survey galaxies are shown together with the accompanying broad band

images (R-band, and unsharp-masked R-band image) in Figs. 22-54

(available only in electronic form at EDP Sciences). However, some

enlargements of selected galaxies with characteristic and spectacular

eDIG morphology are included in logarithmic scale as separate figures in

this section, in order to highlight some finer details of eDIG emission. A

comparison with observations by other researchers from various wavelength

regimes in the context of the disk-halo interaction is made, whenever such

observations were available in the literature.

The H morphology of

NGC24 comprises of planar DIG which is

visible between several bright HII regions in the disk. No

extraplanar DIG is detected which is basically due to the fact that this

galaxy is not perfectly edge-on.

Guthrie (1992)

lists an inclination of 78°. Although the

LFIR/D225 ratio (for a

definition of this expression please cf. Paper I) is quite low, the

S60 / S100 ratio is moderate, and as the

H

morphology of

NGC24 comprises of planar DIG which is

visible between several bright HII regions in the disk. No

extraplanar DIG is detected which is basically due to the fact that this

galaxy is not perfectly edge-on.

Guthrie (1992)

lists an inclination of 78°. Although the

LFIR/D225 ratio (for a

definition of this expression please cf. Paper I) is quite low, the

S60 / S100 ratio is moderate, and as the

H distribution implies

there is considerable star formation activity all over the disk. Additional

evidence comes from a UV-study of nearby galaxies, where the morphology of

the nuclear region in NGC24 was studied

(Maoz et al., 1996).

They classify

NGC24 as a galaxy with star-forming morphology, and several knots or

compact sources can be identified on the UV (~ 2300Å) image,

obtained with the Faint Object Camera (FOC) on-board HST. These regions are

either compact star clusters or individual OB stars.

distribution implies

there is considerable star formation activity all over the disk. Additional

evidence comes from a UV-study of nearby galaxies, where the morphology of

the nuclear region in NGC24 was studied

(Maoz et al., 1996).

They classify

NGC24 as a galaxy with star-forming morphology, and several knots or

compact sources can be identified on the UV (~ 2300Å) image,

obtained with the Faint Object Camera (FOC) on-board HST. These regions are

either compact star clusters or individual OB stars.

UGC260 is shown with another smaller edge-on galaxy, CGCG434-012,

located 2'.4 west of UGC260 (see

Fig. 21), which has a similar

redshift

( v = 47 km

s-1).

Reshetnikov & Combes

(1996)

included them in

their list of tidally-triggered disk thickening galaxies. Indeed, the

morphology in the continuum-subtracted

H

v = 47 km

s-1).

Reshetnikov & Combes

(1996)

included them in

their list of tidally-triggered disk thickening galaxies. Indeed, the

morphology in the continuum-subtracted

H image looks quite

distorted. The HII regions are not aligned and just below

the disk in the very northern part seems to be a small additional galaxy

possibly in the process of merging, or this represents debris tidal tails.

Extraplanar DIG is detected, representing a faint layer, with a few

individual emission patches. The NED lists another galaxy pair between

UGC260 and CGCG434-012, which is barely visible in our R-band

image. We cannot rule out in this particular case, that the eDIG

emission is triggered by interaction of one of the nearby galaxies.

image looks quite

distorted. The HII regions are not aligned and just below

the disk in the very northern part seems to be a small additional galaxy

possibly in the process of merging, or this represents debris tidal tails.

Extraplanar DIG is detected, representing a faint layer, with a few

individual emission patches. The NED lists another galaxy pair between

UGC260 and CGCG434-012, which is barely visible in our R-band

image. We cannot rule out in this particular case, that the eDIG

emission is triggered by interaction of one of the nearby galaxies.

This edge-on galaxy is paired with another edge-on spiral, MCG-2-3-15.

However, these two galaxies are not physically associated, as MCG-2-3-15

has a much higher radial velocity of

vrad = 5765 km s-1.

Hence its H emission is

shifted outside the passband of the used

H

emission is

shifted outside the passband of the used

H filter. MCG-2-3-16 on

the other side is not very prominent

in H

filter. MCG-2-3-16 on

the other side is not very prominent

in H . It is one of our

12 survey galaxies, which has no detectable

FIR flux at 60µm or 100µm at the sensitivity of

IRAS. A small arc

is seen in the western portion, extending about 430 pc north of the disk,

which is not extraplanar. The disk shows a slight asymmetry in thickness

from east to west which might be a projection effect due to a slight

deviation from the edge-on character.

. It is one of our

12 survey galaxies, which has no detectable

FIR flux at 60µm or 100µm at the sensitivity of

IRAS. A small arc

is seen in the western portion, extending about 430 pc north of the disk,

which is not extraplanar. The disk shows a slight asymmetry in thickness

from east to west which might be a projection effect due to a slight

deviation from the edge-on character.

UGC1281 was included in the Effelsberg/VLA radio continuum survey by

Hummel et al. (1991).

However, no radio halo was detected. The

H image did not reveal any extraplanar DIG emission. UGC1281 has also

not been detected by IRAS, so this altogether hints for a low star

formation activity. However, the

H

image did not reveal any extraplanar DIG emission. UGC1281 has also

not been detected by IRAS, so this altogether hints for a low star

formation activity. However, the

H images show several

bright HII regions in the disk which are not aligned. Two

bright emission knots are slightly offset from the plane to the south.

images show several

bright HII regions in the disk which are not aligned. Two

bright emission knots are slightly offset from the plane to the south.

UGC2082 is a northern edge-on spiral galaxy, which is located in the

direction of the NGC1023 group

(Tully, 1980).

It has been investigated on

the basis of a HST survey of large and bright nearby galaxies, studied with

the FOC in the UV-regime at

~ 2300Å

(Maoz et al., 1996).

However,

UGC2082 has not been detected, which is an indication that the SF activity

within this galaxy is very low. That is reflected in our

H

~ 2300Å

(Maoz et al., 1996).

However,

UGC2082 has not been detected, which is an indication that the SF activity

within this galaxy is very low. That is reflected in our

H images as

well. We do not detect significant emission except some HII

regions in the disk. The diagnostic FIR ratios are very low, too.

images as

well. We do not detect significant emission except some HII

regions in the disk. The diagnostic FIR ratios are very low, too.

ESO362-11 has a

LFIR / D225 ratio of ~

2.6, which indicates a moderate SF activity. In our

H images a weak layer of

eDIG is found, but no filaments or plumes are detected. ESO362-11 is

listed in the catalog of Southern Peculiar Galaxies and Associations

(Arp & Madore, 1987)

as AM0514-370, possibly due to a chain of 4 galaxies which

are located in the vicinity of ESO362-11. These are on the outskirts of

our covered field, and therefore are not shown in our appendix image.

Telesco et al. (1988)

report that galaxy interactions enhance the efficiency of SF

activity, which is very likely. However, in the case of ESO362-11 it is

not clear, whether or not the chain of galaxies, which are not in the close

vicinity of ESO362-11, are able to enhance the SF activity.

Coziol et al. (1998)

even have classified ESO362-11 on the basis of their Pico Dos Dias

Survey as a starburst galaxy, based on FIR spectral indices.

images a weak layer of

eDIG is found, but no filaments or plumes are detected. ESO362-11 is

listed in the catalog of Southern Peculiar Galaxies and Associations

(Arp & Madore, 1987)

as AM0514-370, possibly due to a chain of 4 galaxies which

are located in the vicinity of ESO362-11. These are on the outskirts of

our covered field, and therefore are not shown in our appendix image.

Telesco et al. (1988)

report that galaxy interactions enhance the efficiency of SF

activity, which is very likely. However, in the case of ESO362-11 it is

not clear, whether or not the chain of galaxies, which are not in the close

vicinity of ESO362-11, are able to enhance the SF activity.

Coziol et al. (1998)

even have classified ESO362-11 on the basis of their Pico Dos Dias

Survey as a starburst galaxy, based on FIR spectral indices.

This little studied nearby, southern edge-on galaxy has both a moderate

ratio of

LFIR / D225, and

S60 / S100. Its

H morphology reveals an extended layer, not as prominent as in NGC891 or

NGC3044, but still quite intense. The distribution

of the H

morphology reveals an extended layer, not as prominent as in NGC891 or

NGC3044, but still quite intense. The distribution

of the H emission is asymmetric which could be a projection effect, if we were

looking

at the very end of the spiral arm to the south along the line of sight,

whereas the spiral arm to the north could be winded more tightly. Quite

extraordinary is an additional emission component, which shows up in the

whole field around ESO209-9. We speculate that this emission, which is

shown in its fully covered extent in the

H

emission is asymmetric which could be a projection effect, if we were

looking

at the very end of the spiral arm to the south along the line of sight,

whereas the spiral arm to the north could be winded more tightly. Quite

extraordinary is an additional emission component, which shows up in the

whole field around ESO209-9. We speculate that this emission, which is

shown in its fully covered extent in the

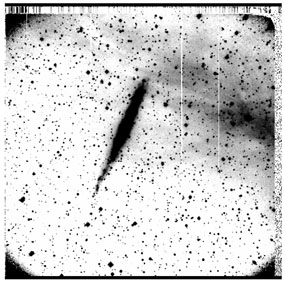

H +continuum image (see

Fig. 3), is of Galactic origin. Quite

remarkably, there is no hint of any

filamentary emission in the broad R-band image. Our first impression

was that this could be straylight from a bright star just outside the

covered CCD field. However, as there was neither a shift (after alignment)

nor a change in the emission pattern noticed in the two individual

H

+continuum image (see

Fig. 3), is of Galactic origin. Quite

remarkably, there is no hint of any

filamentary emission in the broad R-band image. Our first impression

was that this could be straylight from a bright star just outside the

covered CCD field. However, as there was neither a shift (after alignment)

nor a change in the emission pattern noticed in the two individual

H images, which were offset by 20" from one another, and furthermore

such

structures were never recorded prior or after these exposures in other

object frames, we suspect that these structures indeed have a Galactic

origin. A visual inspection of both the blue and red DSS images did not

reveal anything conclusive. Unfortunately, the IR DSS plate of the region

around ESO209-9 is not yet obtained/digitized. The IRAS maps show some

emission in that area, however, the resolution is not sufficient enough to

resolve these structures clearly. A possible explanation could be, that

this emission is Galactic cirrus. This would not be unreasonable, since

ESO209-9 has a galactic latitude of only

b

images, which were offset by 20" from one another, and furthermore

such

structures were never recorded prior or after these exposures in other

object frames, we suspect that these structures indeed have a Galactic

origin. A visual inspection of both the blue and red DSS images did not

reveal anything conclusive. Unfortunately, the IR DSS plate of the region

around ESO209-9 is not yet obtained/digitized. The IRAS maps show some

emission in that area, however, the resolution is not sufficient enough to

resolve these structures clearly. A possible explanation could be, that

this emission is Galactic cirrus. This would not be unreasonable, since

ESO209-9 has a galactic latitude of only

b  -11°.

Unfortunately, this position is just outside the regions studied by the

AAO/UKST H

-11°.

Unfortunately, this position is just outside the regions studied by the

AAO/UKST H survey 4 of the southern

galactic plane (e.g.,

Parker et al., 1999),

which would have been a good

test for comparison. It could also be extended red emission (ERE) in the

diffuse interstellar medium. This ERE was found for high-galactic cirrus

clouds by

Szomoru &

Guhathakurta (1998).

They found a peak of cirrus ERE at

survey 4 of the southern

galactic plane (e.g.,

Parker et al., 1999),

which would have been a good

test for comparison. It could also be extended red emission (ERE) in the

diffuse interstellar medium. This ERE was found for high-galactic cirrus

clouds by

Szomoru &

Guhathakurta (1998).

They found a peak of cirrus ERE at

~

6000Å. However, in order to unravel the true nature of

this filamentary emission, this should be re-investigated by independent

deep H

~

6000Å. However, in order to unravel the true nature of

this filamentary emission, this should be re-investigated by independent

deep H images using a

different instrumental setup, and supplemental

spectroscopy. Fortunately, very recently, we downloaded an available

H

images using a

different instrumental setup, and supplemental

spectroscopy. Fortunately, very recently, we downloaded an available

H image from the

Southern H

image from the

Southern H Sky Survey Atlas

(SHASSA) 5

(see Fig. 2), which

became available very recently. For details on SHASSA we refer to

Gaustad et al. (2001).

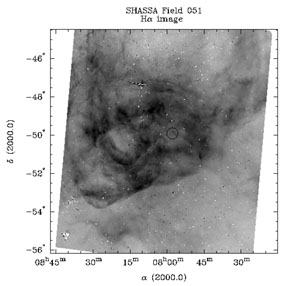

Indeed, the field around the galaxy ESO209-9 shows

detectable H

Sky Survey Atlas

(SHASSA) 5

(see Fig. 2), which

became available very recently. For details on SHASSA we refer to

Gaustad et al. (2001).

Indeed, the field around the galaxy ESO209-9 shows

detectable H emission,

and the H

emission,

and the H morphology is

clearly recovered, despite the spatial resolution of the SHASSA is much

lower than in our images.

morphology is

clearly recovered, despite the spatial resolution of the SHASSA is much

lower than in our images.

|

Figure 2. Field No. 51 of the Southern

H |

|

Figure 3. Field around ESO209-9, showing

very structured, cirrus-like galactic emission in this

H |

NGC3003 has been investigated spectroscopically by

(Ho et al., 1995) in

search of dwarf Seyfert nuclei, who concluded, based on a detected

broad emission complex centered at

4650Å, that this

galaxy is a Wolf-Rayet galaxy. NGC3003 has a modest

LFIR / D225 ratio

(1.65), however, the

S60 / S100 ratio of ~ 0.34 hints

that there

is some SF activity due to enhanced dust temperatures. Furthermore, due to

the slight deviation from its edge-on character, no extraplanar emission

can be identified reliably. The

H

4650Å, that this

galaxy is a Wolf-Rayet galaxy. NGC3003 has a modest

LFIR / D225 ratio

(1.65), however, the

S60 / S100 ratio of ~ 0.34 hints

that there

is some SF activity due to enhanced dust temperatures. Furthermore, due to

the slight deviation from its edge-on character, no extraplanar emission

can be identified reliably. The

H distribution, however,

reveals strong planar DIG, consistent with the observations by

Hoopes et al. (1999).

Several bright emission knots can be discerned. About four decades ago a SN

has been detected 34"E, and 17"N of the nucleus (SN1961F).

distribution, however,

reveals strong planar DIG, consistent with the observations by

Hoopes et al. (1999).

Several bright emission knots can be discerned. About four decades ago a SN

has been detected 34"E, and 17"N of the nucleus (SN1961F).

This is one of the galaxies with the highest LFIR / D225 ratio in our survey (13.8). The S60 / S100 ratio is also quite high (0.37), suggesting enhanced SF activity. Indeed, there are many bright HII regions visible in the disk, preferentially located in the spiral arms, which are slightly recognizable, due to the small deviation from its edge-on inclination. A faint eDIG layer is visible. There is a slight asymmetry between the northern part and the southern part of the galaxy (i.e. the two spiral arms) discernable. NGC3221 has also been investigated in the radio regime (radio continuum), where Irwin et al. (2000) detected extended disk emission. It is noteworthy to mention that a SN has been detected (SN1961L) in NGC3221.

NGC3501 was observed with the Effelsberg 100m radio dish at 5GHz in a

survey to detect radio halos in edge-on galaxies, related to SF driven

outflows (Hummel et al.,

1991).

No extended radio emission has been detected.

The optical appearance, based on our

H imaging reveals also a

quiescent galaxy, with no extraplanar emission. Besides some modest

HII regions in the disk, its morphology looks rather

inconspicuous. In fact, it is also one of the 12 galaxies in our survey

which has no FIR detections.

imaging reveals also a

quiescent galaxy, with no extraplanar emission. Besides some modest

HII regions in the disk, its morphology looks rather

inconspicuous. In fact, it is also one of the 12 galaxies in our survey

which has no FIR detections.

This edge-on spiral galaxy has been included in the catalog of Markarian

galaxies as <

ahref="/cgi-bin/objsearch?objname=Mrk+1443&extend=no&out_csys=Equatorial&out_equinox=J2000.0&obj_sort=RA+or+Longitude&of=pre_text&zv_breaker=30000.0&list_limit=5&img_stamp=YES"

target="ads_dw">Mrk1443

(Mazarella &

Balzano, 1986).

The broadband R image shows a prominent

bulge and indicates a slight warp which was also noticed by

(Sánchez-Saavedra et

al., 1990).

In our H image it

becomes even more obvious that the disk is warped.

There is some extraplanar DIG detected, basically around the central

regions, where extended emission seems to be ejected from the nuclear

region. There is, besides the nucleus, one bright emission region,

presumably consisting of several smaller components, and several fainter

knots visible in the disk. Although the

LFIR / D225 is quite

moderate (1.4), NGC3600 has a relatively high

S60 / S100 ratio of

~ 0.44. Spectroscopy of the nuclear region reveals strong emission from

the Balmer lines (H

image it

becomes even more obvious that the disk is warped.

There is some extraplanar DIG detected, basically around the central

regions, where extended emission seems to be ejected from the nuclear

region. There is, besides the nucleus, one bright emission region,

presumably consisting of several smaller components, and several fainter

knots visible in the disk. Although the

LFIR / D225 is quite

moderate (1.4), NGC3600 has a relatively high

S60 / S100 ratio of

~ 0.44. Spectroscopy of the nuclear region reveals strong emission from

the Balmer lines (H ,

H

,

H ), as well

as from several forbidden low ionization lines, such as

[NII], and [SII]

(Ho et al., 1995).

We show a detailed view of NGC3600 in Fig. 4.

), as well

as from several forbidden low ionization lines, such as

[NII], and [SII]

(Ho et al., 1995).

We show a detailed view of NGC3600 in Fig. 4.

|

Figure 4. Extraplanar DIG layer in NGC3600. The eDIG morphology is reminiscent of a starburst galaxy. The field of view measures ~ 11.3 kpc × 11.3 kpc. Orientation: N is to the top and E to the left. |

NGC3628 is a member of the Leo triplet, which also includes

NGC3623 and NGC3627. It is a starburst galaxy with a very prominent dust

lane, which obscures most parts of the emission in the galactic

midplane. It

has been studied extensively in almost all wavelength regimes, and has also

been the target for a multi-wavelength study in the context of the

disk-halo connection. Radio continuum observations

(Schlickeiser et al.,

1984)

reveal extended emission, and in the X-ray regime a T ~ 2 ×

106K,

extended halo has been detected by sensitive PSPC observations with ROSAT

(Dahlem et al., 1996).

Prominent X-ray emission, tracing the collimated outflow

from the nuclear starburst, was found to be spatially correlated with the

H plume

(Fabbiano et al., 1990).

Extraplanar dust has already been detected

(Howk & Savage,

1999;

Rossa, 2001).

We also observed extended emission from the nuclear

outflow, localized extended emission (filamentary), and several extraplanar

HII regions.

plume

(Fabbiano et al., 1990).

Extraplanar dust has already been detected

(Howk & Savage,

1999;

Rossa, 2001).

We also observed extended emission from the nuclear

outflow, localized extended emission (filamentary), and several extraplanar

HII regions.

NGC3877 is a northern edge-on spiral galaxy, which ranks among the top 15

galaxies of our survey, according to the SFR per unit area. A SFR from

observations in the UV has been derived, which yielded

0.55 M yr-1

(Donas et al., 1987).

A nuclear spectrum reveals quite strong emission of

H

yr-1

(Donas et al., 1987).

A nuclear spectrum reveals quite strong emission of

H (Ho et al., 1995),

whereas H

(Ho et al., 1995),

whereas H , and the

[NII] lines are also clearly detected. Just recently a SN of

type II has been detected in NGC3877, namely SN1998S

(Filippenko & Moran,

1998). In

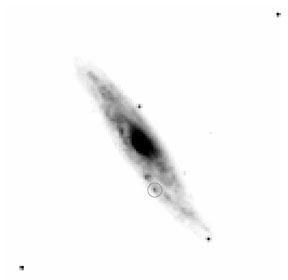

Fig. 6 we show our broadband R image, which was

obtained almost a year after

its discovery. The SN (marked by a circle), although considerably fainter,

is still visible in our image.

Niklas et al. (1995)

report a

, and the

[NII] lines are also clearly detected. Just recently a SN of

type II has been detected in NGC3877, namely SN1998S

(Filippenko & Moran,

1998). In

Fig. 6 we show our broadband R image, which was

obtained almost a year after

its discovery. The SN (marked by a circle), although considerably fainter,

is still visible in our image.

Niklas et al. (1995)

report a  2.8cm flux

for NGC3877 of

Stot = 23 ± 8 mJy. However, no radio map was shown,

and they did not comment further on this galaxy. The

H

2.8cm flux

for NGC3877 of

Stot = 23 ± 8 mJy. However, no radio map was shown,

and they did not comment further on this galaxy. The

H morphology,

as seen in our images, reveal extended emission with some small filaments

and plumes. Quite remarkable is the distribution of very strong

HII regions and knots which are seen all over the disk

(cf. Fig. 5). The nuclear region is very compact in

H

morphology,

as seen in our images, reveal extended emission with some small filaments

and plumes. Quite remarkable is the distribution of very strong

HII regions and knots which are seen all over the disk

(cf. Fig. 5). The nuclear region is very compact in

H .

.

|

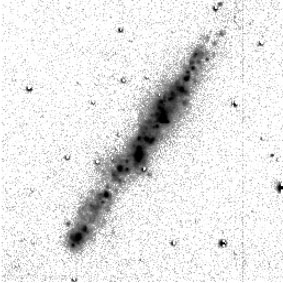

Figure 5. Extraplanar DIG layer in NGC3877

seen in this continuum subtracted

H |

|

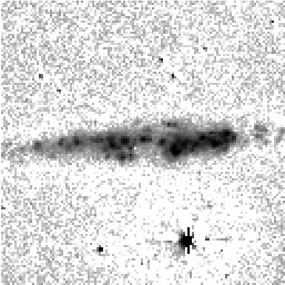

Figure 6. SN1998S (marked by a circle) in NGC3877. Our R-band image was obtained 354 days after the discovery of SN1998S. Image size and orientation is same as above. |

Another Virgo cluster spiral, NGC4216 has been classified as

a WR-galaxy, based on detected

HeII 4686

emission from a few regions within NGC4216

(Schaerer et al., 1999).

Pogge (1989b)

investigated

the morphology of the nuclear emission, and concluded it as diffuse, while

the circumnuclear region was characterized as faint and patchy. There is

nuclear emission detected from X-rays

(Fabbiano et al., 1992).

Maoz et al. (1996)

did not detect UV emission in NGC4216 in their HST survey. Our

H

4686

emission from a few regions within NGC4216

(Schaerer et al., 1999).

Pogge (1989b)

investigated

the morphology of the nuclear emission, and concluded it as diffuse, while

the circumnuclear region was characterized as faint and patchy. There is

nuclear emission detected from X-rays

(Fabbiano et al., 1992).

Maoz et al. (1996)

did not detect UV emission in NGC4216 in their HST survey. Our

H image did

not reveal extraplanar emission. The nucleus is the strongest source,

whereas several smaller HII regions in the outer spiral arm

contribute also to the

H

image did

not reveal extraplanar emission. The nucleus is the strongest source,

whereas several smaller HII regions in the outer spiral arm

contribute also to the

H emission.

emission.

NGC4235 has been classified as a Seyfert galaxy of type 1

(Weedman, 1978),

and has no physical companion

(Dahari, 1984).

Pogge (1989a) has

studied the nuclear environment using narrowband imaging of

H and

[OIII]. He found a bright nucleus with an extended region

towards the NE direction at P.A. ~ 48°, which extends ~ 4.4".

Neither disk HII regions were detected, nor ionized gas

above the plane. Radio continuum observations

(Hummel et al., 1991)

also did not find

evidence for extended emission. In the X-ray regime the strong nuclear

region is detected with a luminosity of

1.55 × 1042 erg s-1

(Fabbiano et al., 1992).

In a study of large-scale outflows in edge-on Seyfert galaxies

Colbert et al. (1996b)

found no double peaked line profiles, or any

evidence for extended line regions, and no minor axis emission,

too. However, on radio continuum images obtained with the VLA at 4.9 GHz

there was a

diffuse, bubble-like, extended structure (~ 9 kpc) found in addition

to the unresolved nucleus

(Colbert et al., 1996a).

Our H

and

[OIII]. He found a bright nucleus with an extended region

towards the NE direction at P.A. ~ 48°, which extends ~ 4.4".

Neither disk HII regions were detected, nor ionized gas

above the plane. Radio continuum observations

(Hummel et al., 1991)

also did not find

evidence for extended emission. In the X-ray regime the strong nuclear

region is detected with a luminosity of

1.55 × 1042 erg s-1

(Fabbiano et al., 1992).

In a study of large-scale outflows in edge-on Seyfert galaxies

Colbert et al. (1996b)

found no double peaked line profiles, or any

evidence for extended line regions, and no minor axis emission,

too. However, on radio continuum images obtained with the VLA at 4.9 GHz

there was a

diffuse, bubble-like, extended structure (~ 9 kpc) found in addition

to the unresolved nucleus

(Colbert et al., 1996a).

Our H image reveals a

bright nucleus with a faint extended layer, which is restricted to the

circumnuclear

part. NE of the nucleus a depression is visible, possibly due to absorbing

dust, as already noted by

Pogge (1989a),

and easily visible in the broad band HST image by

Malkan et al. (1998).

This is one of the very few Seyfert galaxies that

appear in our survey. The role of minor axis outflows in Seyfert galaxies,

and thus the contribution to the IGM enrichment and heating still has to be

explored.

image reveals a

bright nucleus with a faint extended layer, which is restricted to the

circumnuclear

part. NE of the nucleus a depression is visible, possibly due to absorbing

dust, as already noted by

Pogge (1989a),

and easily visible in the broad band HST image by

Malkan et al. (1998).

This is one of the very few Seyfert galaxies that

appear in our survey. The role of minor axis outflows in Seyfert galaxies,

and thus the contribution to the IGM enrichment and heating still has to be

explored.

NGC4388 has been identified as the first Seyfert2 galaxy in the Virgo cluster (Phillips & Malin, 1982), and has been studied extensively in various wavelength regimes, including optical line imaging and spectroscopy (e.g., Keel, 1983; Corbin et al., 1988; Pogge, 1988), radio continuum (e.g., Stone et al., 1988; Hummel & Saikia, 1991), and in the high energy waveband extended soft X-ray emission out to a radius of 4.5 kpc has been reported (Matt et al., 1994). From the optical morphology and kinematics it was derived that NGC4388 possesses complex gas kinematics and is composed of several nucleated emission line regions. A prominent feature reaches out to ~ 18" at P.A. ~ 10° (Heckman et al., 1983). The radio continuum maps revealed a double peaked radio source close to the optical nucleus plus a cloud of radio emitting material, apparently ejected from the nucleus (e.g., Stone et al., 1988; Irwin et al., 2000).

Some speculation on the true membership to the Virgo cluster exists, although

NGC4388 is located near the core of the Virgo cluster. This is because of

its relatively high systemic velocity. However, most authors assume it is a

member of the Virgo cluster. Therefore, ram pressure stripping

seems to

play a role as NGC4388 interacts with the ambient intracluster medium (ICM).

Optical narrowband imaging in

H and

[OIII] has

revealed that the morphology of the extended ionized gas is composed of two

opposed radiation cones

(Pogge, 1988),

which give rise to a hidden

Seyfert1 nucleus, as favored in the unification scheme of

AGN. Recent investigations of NGC4388 using Fabry-Perot imaging techniques

have revealed a complex of highly ionized gas ~ 4 kpc above the disk

(Veilleux et al., 1999).

They found blueshifted velocities of

50 - 250 km s-1 NE of the nucleus. Furthermore they assume

the velocity of

the extraplanar gas to be unaffected by the inferred supersonic motion of

NGC4388 through the ICM of the Virgo cluster, and suggest that the galaxy

and high-| z| gas lies behind the Mach cone.

and

[OIII] has

revealed that the morphology of the extended ionized gas is composed of two

opposed radiation cones

(Pogge, 1988),

which give rise to a hidden

Seyfert1 nucleus, as favored in the unification scheme of

AGN. Recent investigations of NGC4388 using Fabry-Perot imaging techniques

have revealed a complex of highly ionized gas ~ 4 kpc above the disk

(Veilleux et al., 1999).

They found blueshifted velocities of

50 - 250 km s-1 NE of the nucleus. Furthermore they assume

the velocity of

the extraplanar gas to be unaffected by the inferred supersonic motion of

NGC4388 through the ICM of the Virgo cluster, and suggest that the galaxy

and high-| z| gas lies behind the Mach cone.

Our narrowband imaging of NGC4388 (see Fig. 7)

reveals also extended

emission which is pointing away from the galactic disk to the halo in

the NE direction. Furthermore a faint eDIG layer is visible. Very

recently deep

H images obtained with

the Subaru telescope revealed very extended emission-line region in

H

images obtained with

the Subaru telescope revealed very extended emission-line region in

H and

[OIII] at distances of up to ~ 35 kpc

(Yoshida et al., 2002).

and

[OIII] at distances of up to ~ 35 kpc

(Yoshida et al., 2002).

|

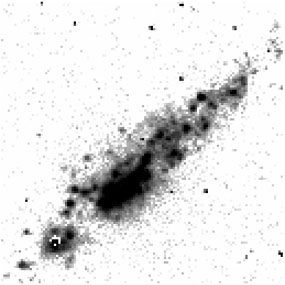

Figure 7. Continuum subtracted

H |

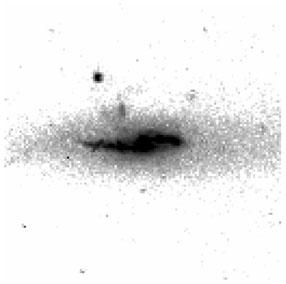

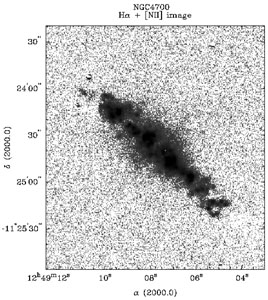

NGC4700 has been listed as a HII region galaxy in the list

of Rodriguez Espinosa et

al. (1987),

while Hewitt &

Burbidge (1991)

list it as a Seyfert2 galaxy. It

has been included in the HST imaging survey of nearby AGN

(Malkan et al., 1998).

NGC4700 has a relatively large ratio of

S60 / S100 of ~ 0.51,

making it a promising candidate with a potential DIG halo according to the

diagnostic DIG diagram. Indeed, a relatively bright, and extended gaseous

halo with a maximum extent of 2.0 kpc above/below the galactic plane is

discovered. One of the filaments can even be traced farther out to

~ 3 kpc. The morphology of DIG in NGC4700 is asymmetrical, with the

eastern and middle part being most prominent. Five distinct bright

HII region complexes, which are composed of several

individual

smaller regions across the disk, can be discerned. Some prominent filaments

above active regions protrude from the disk into the halo. A small

number of

bright HII regions is seen in this part of the disk, and the

maximum extent of the eDIG is visible above those regions. The western part

of the galaxy is lacking in bright HII regions, hence the

suppressed extend of the halo in this western part. NGC4700 also bears an

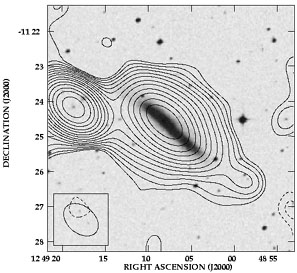

extended radio halo (radio thick disk), with the maximum extent

correspondingly on the same position above the disk

(Dahlem et al., 2001),

although slightly more extended in the radio continuum image as in our

H image (see Figs. 8 + 9).

image (see Figs. 8 + 9).

|

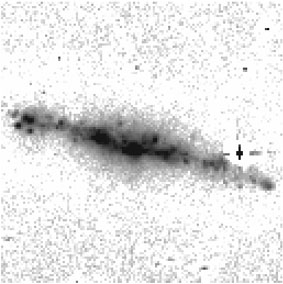

Figure 8. A detailed

H |

|

Figure 9. The extended radio halo of

NGC4700 at |

NGC4945 is a well studied southern edge-on spiral galaxy, which belongs to the Centaurus group. It has been studied at various wavelengths, including the visual, IR, and radio regime. Heckman et al. (1990) found evidence for a starburst driven superwind in NGC4945, and Moorwood & Olivia (1994) derive a ~ 400 pc size starburst in addition to the presence of a visually absorbed Seyfert nucleus. They conclude that NGC4945 is in an advanced stage of evolution from a starburst to a Seyfert galaxy. Extended emission from the disk was detected by radio continuum observations (Harnett et al., 1989; Colbert et al., 1996a), reaching a diameter of ~ 23 kpc. X-ray emission was detected from the nuclear region, however, no extended emission was found in ROSAT PSPC observations (Colbert et al., 1998), probably due to quite large absorbing columns (NH = 1.5 × 1021 cm-2), as NGC4945 is situated near the galactic plane (b ~ 13°). This decreases the sensitivity for the soft X-ray regime.

NGC4945 is one of the few starburst galaxies that we have included in our

H survey, and it is no

surprise that it has the second highest

LFIR / D225 ratio of ~

14.8 of our studied galaxies. Already investigated by

Lehnert & Heckman

(1995),

NGC4945 shows strong extraplanar DIG with

many filaments protruding from the disk into the halo. There are at least

two bright filaments on either side of the disk visible on our narrowband

images. Several prominent dust patches, which obscure some parts of the

emission south of the galactic plane is a further characteristic pattern

for this galaxy. In Fig. 10 we show an

enlargement of the middle part, which

nicely shows the outflow cone from the nuclear starburst.

survey, and it is no

surprise that it has the second highest

LFIR / D225 ratio of ~

14.8 of our studied galaxies. Already investigated by

Lehnert & Heckman

(1995),

NGC4945 shows strong extraplanar DIG with

many filaments protruding from the disk into the halo. There are at least

two bright filaments on either side of the disk visible on our narrowband

images. Several prominent dust patches, which obscure some parts of the

emission south of the galactic plane is a further characteristic pattern

for this galaxy. In Fig. 10 we show an

enlargement of the middle part, which

nicely shows the outflow cone from the nuclear starburst.

|

Figure 10. A zoom onto the outflowing cone

in this H |

This northern edge-on galaxy is part of the LGG361 group

(Garcia, 1993),

which teams up with NGC5289, which is located ~ 13' to the south, and

has a velocity difference to NGC5290 of ~ 67 km s-1

(Huchra et al., 1983).

In the optical NGC5290's most striking character is a box-shaped bulge

(de Souza & Dos

Anjos, 1987).

The LFIR / D225 ratio is

moderate (~ 2.6), and NGC5290 shows some extended emission, where a

faint layer is detected, and some filaments, basically coming from the

nuclear region and reaching into the halo, can be discerned (see

Fig. 11). The morphology that is visible on the

H image resembles those

of a starburst galaxy, although NGC5290 has no starburst-like FIR

parameters, as the S60 / S100 ratio

is considerably lower (0.31).

image resembles those

of a starburst galaxy, although NGC5290 has no starburst-like FIR

parameters, as the S60 / S100 ratio

is considerably lower (0.31).

|

Figure 11. Continuum subtracted

H |

Another northern edge-on spiral, NGC5297 forms a binary galaxy with

NGC5296 (Turner, 1976),

which is separated by about 1.5' from NGC5297,

and has a velocity difference of

v

v

360 km s-1.

Another interesting source is also located in the direct vicinity, a quasar

of V = 19.3 mag

(Arp, 1976).

This quasar ([HB89]1342+440), which has a

redshift of z = 0.963, is located 2.5' to the SW. Arp reports on

a luminous extension from NGC5236 pointing at the QSO, which

Sharp (1990) did not

confirm. However,

Sharp (1990)

did comment on the unusually bright

off-center secondary nucleus of NGC5296. The QSO is marked by a circle in

our R-band image in Fig. 40. The outer spiral arms of NGC5297 show

evidence of perturbation by the S0 companion, as reported by

(Rampazzo et al., 1995).

360 km s-1.

Another interesting source is also located in the direct vicinity, a quasar

of V = 19.3 mag

(Arp, 1976).

This quasar ([HB89]1342+440), which has a

redshift of z = 0.963, is located 2.5' to the SW. Arp reports on

a luminous extension from NGC5236 pointing at the QSO, which

Sharp (1990) did not

confirm. However,

Sharp (1990)

did comment on the unusually bright

off-center secondary nucleus of NGC5296. The QSO is marked by a circle in

our R-band image in Fig. 40. The outer spiral arms of NGC5297 show

evidence of perturbation by the S0 companion, as reported by

(Rampazzo et al., 1995).

Radio continuum observations of NGC5297 have been performed

(Irwin et al., 2000; Hummel et al., 1985; Irwin et al., 1999). While

Irwin et al. (1999)

claims extended radio continuum

emission from NGC5297, still, higher resolution observations show only

very weak emission

(Irwin et al., 2000).

Our H image does not

reveal any

extraplanar emission. Thus, we do not see enhanced SF activity due to the

interaction with the companion galaxy in this case. The

LFIR / D225 ratio is

moderate. We also note, that this galaxy actually is not

perfectly edge-on.

image does not

reveal any

extraplanar emission. Thus, we do not see enhanced SF activity due to the

interaction with the companion galaxy in this case. The

LFIR / D225 ratio is

moderate. We also note, that this galaxy actually is not

perfectly edge-on.

From HI observations it was found that NGC5775 is an

interacting galaxy with its neighbor face-on spiral NGC5774. Emission

along a bridge has been detected, although no tidal arms are discovered

(Irwin, 1994).

NGC5775 is a good studied northern edge-on galaxy in the

disk-halo context, which has been imaged in

H (Tüllmann et al.,

2000;

Collins et al., 2000;

Lehnert & Heckman,

1995),

where extraplanar emission was detected out to

over 5 kpc above the galactic plane. It is the galaxy with the highest

LFIR / D225 ratio in our

sample and is a starburst-type galaxy,

although no clear indications exist on a nuclear starburst. A bright halo

with individual filaments superposed in a prominent X-shape are

discovered on our narrowband image, consistent with earlier observations,

mentioned above. Extraplanar DIG has been detected spectroscopically out to

9 kpc

(Tüllmann et al.,

2000;

Rand, 2000),

and extended radio continuum emission has been detected as well

(Duric et al., 1998;

Hummel et al., 1991).

Extended X-ray emission coexistent

with a radio continuum spur and optical filament was discovered on ROSAT

PSPC archival images

(Rossa, 2001).

(Tüllmann et al.,

2000;

Collins et al., 2000;

Lehnert & Heckman,

1995),

where extraplanar emission was detected out to

over 5 kpc above the galactic plane. It is the galaxy with the highest

LFIR / D225 ratio in our

sample and is a starburst-type galaxy,

although no clear indications exist on a nuclear starburst. A bright halo

with individual filaments superposed in a prominent X-shape are

discovered on our narrowband image, consistent with earlier observations,

mentioned above. Extraplanar DIG has been detected spectroscopically out to

9 kpc

(Tüllmann et al.,

2000;

Rand, 2000),

and extended radio continuum emission has been detected as well

(Duric et al., 1998;

Hummel et al., 1991).

Extended X-ray emission coexistent

with a radio continuum spur and optical filament was discovered on ROSAT

PSPC archival images

(Rossa, 2001).

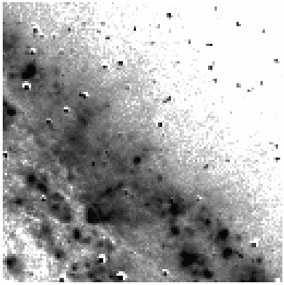

ESO274-1 belongs to the Cen A group of galaxies, and

Banks et al. (1999)

derive a HI mass of 430 × 106

M , ranking

on position five of the Cen A group. This little studied southern

edge-on galaxy was included in the recent list of dwarf galaxies by

Cote et al. (1997),

who studied new discovered dwarf galaxies in the nearest

groups of galaxies. From optical inspection of the DSS images, it is

obvious

that this galaxy has a low surface brightness. It is the galaxy with the

lowest LFIR / D225 ratio

among the IRAS detected galaxies in our sample (0.19)! Quite remarkably

however, the

S60 / S100 ratio is among

the highest in our sample, making ESO274-1 a promising candidate in search

for eDIG. We show in Fig. 12 an enlargement of

the most active SF regions,

which show strong local extended emission. The SW and middle part is most

prominent, whereas there are regions in the NE part, where this galaxy

(superposed by a crowded field of foreground stars) is almost invisible in

H

, ranking

on position five of the Cen A group. This little studied southern

edge-on galaxy was included in the recent list of dwarf galaxies by

Cote et al. (1997),

who studied new discovered dwarf galaxies in the nearest

groups of galaxies. From optical inspection of the DSS images, it is

obvious

that this galaxy has a low surface brightness. It is the galaxy with the

lowest LFIR / D225 ratio

among the IRAS detected galaxies in our sample (0.19)! Quite remarkably

however, the

S60 / S100 ratio is among

the highest in our sample, making ESO274-1 a promising candidate in search

for eDIG. We show in Fig. 12 an enlargement of

the most active SF regions,

which show strong local extended emission. The SW and middle part is most

prominent, whereas there are regions in the NE part, where this galaxy

(superposed by a crowded field of foreground stars) is almost invisible in

H .

.

|

Figure 12. Prominent extraplanar emission

regions in this continuum subtracted

H |

This is a perfect edge-on galaxy, and it is the only one of type S0-a in

our sample. It was only included because of its classification as type

Sa in the NED. It shows a strong dust lane, and a strikingly bright, and

extended bulge in the R-band image. An upper radio continuum flux limit of

20 mJy at  11cm has been

given by

Sadler (1984),

and a upper flux limit of F[N II] < 1.6 ×

10-14 erg s-1 cm-2 has been derived by

Phillips et al. (1986).

We detect

no extended emission in ESO142-19. Even the disk is almost invisible on

our H

11cm has been

given by

Sadler (1984),

and a upper flux limit of F[N II] < 1.6 ×

10-14 erg s-1 cm-2 has been derived by

Phillips et al. (1986).

We detect

no extended emission in ESO142-19. Even the disk is almost invisible on

our H image.

image.

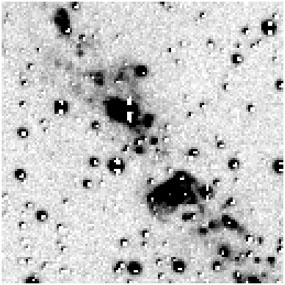

IC5052 is a late-type spiral with classifications Scd or Sd. Radio

emission detected by

35cm observations

revealed an unusually

double peaked radio emission complex associated with the disk, which was

not coming from the nucleus

(Harnett & Reynolds,

1991).

35cm observations

revealed an unusually

double peaked radio emission complex associated with the disk, which was

not coming from the nucleus

(Harnett & Reynolds,

1991).

Our H image reveals a

bright layer of extraplanar DIG superposed by

individual filaments and shells (see Fig. 13).

There is a depression in the

H

image reveals a

bright layer of extraplanar DIG superposed by

individual filaments and shells (see Fig. 13).

There is a depression in the

H distribution noticed

in the southern part of the galaxy, due to

significant dust absorption, which almost separates the galaxy in two

parts. An asymmetrical distribution is also visible in the R-band

image. The southern edge is dominated by

H

distribution noticed

in the southern part of the galaxy, due to

significant dust absorption, which almost separates the galaxy in two

parts. An asymmetrical distribution is also visible in the R-band

image. The southern edge is dominated by

H emission, whereas the

broadband

image shows almost no intensity. Several arcs and shells make this galaxy a

good target for further high resolution studies.

emission, whereas the

broadband

image shows almost no intensity. Several arcs and shells make this galaxy a

good target for further high resolution studies.

|

Figure 13. Continuum subtracted

H |

Pa observations with

NICMOS 2 HST

(Böker et al.,

1999)

showed excess

emission of an isolated region in the disk-halo interface, slightly offset

from the disk, which is possibly associated with one of the brighter

emission regions in the southern part of our

H

observations with

NICMOS 2 HST

(Böker et al.,

1999)

showed excess

emission of an isolated region in the disk-halo interface, slightly offset

from the disk, which is possibly associated with one of the brighter

emission regions in the southern part of our

H image. The diagnostic

ratios are both moderate, so it is quite remarkable that extended DIG

emission is detected in that abundance in IC5052.

image. The diagnostic

ratios are both moderate, so it is quite remarkable that extended DIG

emission is detected in that abundance in IC5052.

NGC7064 is a HII region like galaxy

(Kirhakos & Steiner,

1990). Radio

emission has been detected at

35 cm

(Harnett & Reynolds,

1991),

which extends

over the inner disk with a maximum intensity at the nucleus. The disk

emission is more pronounced to the east, which corresponds to the optical

emission distribution. They further show in their map a weak extension to

the south, which apparently has no optical counterpart. NGC7064 has also

been detected in the ROSAT All Sky Survey (RASS), which was included in a

study of IRAS galaxies

(Boller et al., 1998).

The X-ray intensity maximum is

offset from the IRAS position (nucleus). Furthermore, weaker emission is

detected to the south of NGC7064 at larger distances far out in the halo

region. Presently it is not clear if it is related to NGC7064. In

Fig. 14

we show our H

35 cm

(Harnett & Reynolds,

1991),

which extends

over the inner disk with a maximum intensity at the nucleus. The disk

emission is more pronounced to the east, which corresponds to the optical

emission distribution. They further show in their map a weak extension to

the south, which apparently has no optical counterpart. NGC7064 has also

been detected in the ROSAT All Sky Survey (RASS), which was included in a

study of IRAS galaxies

(Boller et al., 1998).

The X-ray intensity maximum is

offset from the IRAS position (nucleus). Furthermore, weaker emission is

detected to the south of NGC7064 at larger distances far out in the halo

region. Presently it is not clear if it is related to NGC7064. In

Fig. 14

we show our H image,

scaled logarithmically, to show the faint halo.

A few emission patches and plumes are visible to the south of the disk, and

also in the northern part. The disk emission is asymmetrically distributed,

with the eastern part being most prominent. There is a prominent hole in

the southern disk, bisecting the disk almost entirely. In our

logarithmically scaled image the hole is almost filled with diffuse

emission, but its intensity is weaker than in the eastern and western

part of the disk-halo interface. Although the

LFIR / D225 ratio is

quite low, it should be noted that the

S60 / S100 ratio is the highest in

our sample.

image,

scaled logarithmically, to show the faint halo.

A few emission patches and plumes are visible to the south of the disk, and

also in the northern part. The disk emission is asymmetrically distributed,

with the eastern part being most prominent. There is a prominent hole in

the southern disk, bisecting the disk almost entirely. In our

logarithmically scaled image the hole is almost filled with diffuse

emission, but its intensity is weaker than in the eastern and western

part of the disk-halo interface. Although the

LFIR / D225 ratio is

quite low, it should be noted that the

S60 / S100 ratio is the highest in

our sample.

|

Figure 14. Continuum subtracted

H |

This southern edge-on spiral has radio continuum detections at

35cm (Harnett &

Reynolds, 1985).

The radio emission follows the plane of the galaxy,

and extends above it in two distinct spurs out to a distance of

~ 1.5 kpc. The radio peak coincide with the optical nucleus, however,

they note no obvious nuclear radio source. Our R-band image shows that a

prominent dust lane with patchy structures runs across most parts of

the disk offset slightly to the north. It is very irregular, unlike most

other prominent dust lanes, such as in NGC891 or IC2531. The

H

35cm (Harnett &

Reynolds, 1985).

The radio emission follows the plane of the galaxy,

and extends above it in two distinct spurs out to a distance of

~ 1.5 kpc. The radio peak coincide with the optical nucleus, however,

they note no obvious nuclear radio source. Our R-band image shows that a

prominent dust lane with patchy structures runs across most parts of

the disk offset slightly to the north. It is very irregular, unlike most

other prominent dust lanes, such as in NGC891 or IC2531. The

H image (Fig. 15) reveals a faint halo, in

addition to some filaments and

extended emission in the form of knots. The northeastern part of the galaxy

has the highest intensity in emission, whereas the southern half is almost

absent, except very few emission patches (HII regions) in

the disk. The filaments protrude basically from the nuclear region into the

halo. It should be noted that the extended radio continuum emission is

coincident with the

H

image (Fig. 15) reveals a faint halo, in

addition to some filaments and

extended emission in the form of knots. The northeastern part of the galaxy

has the highest intensity in emission, whereas the southern half is almost

absent, except very few emission patches (HII regions) in

the disk. The filaments protrude basically from the nuclear region into the

halo. It should be noted that the extended radio continuum emission is

coincident with the

H extended emission.

extended emission.

|

Figure 15. Continuum subtracted

H |

NGC7184 was detected in the radio regime at

20cm continuum

emission (Condon, 1987),

and bears a double peaked brightness distribution. This was confirmed by

Harnett & Reynolds

(1991),

who detected two maxima at

20cm continuum

emission (Condon, 1987),

and bears a double peaked brightness distribution. This was confirmed by

Harnett & Reynolds

(1991),

who detected two maxima at

35cm. NGC7184 is

located at a projected distance of 163 kpc

(20.9') to NGC7185, as quoted by

Kollatschny & Fricke

(1989),

who studied the group

environment of Seyfert galaxies. A peculiar supernova was detected in

NGC7184, named SN1984N

(Barbon et al., 1999).

Our H

35cm. NGC7184 is

located at a projected distance of 163 kpc

(20.9') to NGC7185, as quoted by

Kollatschny & Fricke

(1989),

who studied the group

environment of Seyfert galaxies. A peculiar supernova was detected in

NGC7184, named SN1984N

(Barbon et al., 1999).

Our H image did not

show any extraplanar emission, which might be due to the fact, that

NGC7184 is not perfectly edge-on. The outstanding feature in NGC7184 is

the inner ring, which is also prominently seen on the R-band image. There

is a well pronounced sub-structure visible, and several HII

regions can be discerned in the ring and in the outer spiral arms.

image did not

show any extraplanar emission, which might be due to the fact, that

NGC7184 is not perfectly edge-on. The outstanding feature in NGC7184 is

the inner ring, which is also prominently seen on the R-band image. There

is a well pronounced sub-structure visible, and several HII

regions can be discerned in the ring and in the outer spiral arms.

The late type spiral NGC7339 is accompanied by the galaxy NGC7332 at a

projected distance of 5.2', the latter one being a peculiar S0 galaxy,

which has a velocity difference of

v = - 141 km

s-1 in

comparison to NGC7339. A supernova (SN1989L) has been discovered in

NGC7339

(Barbon et al., 1999).

Several bright, and compact knots are

seen in our H

v = - 141 km

s-1 in

comparison to NGC7339. A supernova (SN1989L) has been discovered in

NGC7339

(Barbon et al., 1999).

Several bright, and compact knots are

seen in our H image, but

no extraplanar emission is detected.

NGC7332, which is also visible on our frame, is

completely absent in H

image, but

no extraplanar emission is detected.

NGC7332, which is also visible on our frame, is

completely absent in H .

.

UGC12281 has already been studied in the DIG context a few years ago by Pildis et al. (1994). They claim to have detected two extraplanar emission line features (discrete clouds), and a clumpy plume. We can confirm the presence of these two clouds, and the plume is also marginally detected in our image, which suffers from low S/N.

This southern edge-on spiral was detected with the VLA at

= 1.49 GHz

(Condon et al.,

1987), and

Maoz et al. (1996)

have conducted UV observations at

(

= 1.49 GHz

(Condon et al.,

1987), and

Maoz et al. (1996)

have conducted UV observations at

( 2300Å)

of the inner 22" × 22" region with the HST,

where they detected a star-forming morphology in several distinct

regions (knots). Our

H

2300Å)

of the inner 22" × 22" region with the HST,

where they detected a star-forming morphology in several distinct

regions (knots). Our

H image

(Fig. 16) reveals an extended DIG layer

with individual plumes and faint filaments superposed. The disk emission is

composed of several distinct emission complexes, clustered basically in

three regions (nucleus + two regions within the disk), and some fainter

regions in the outskirts of the disk.

image

(Fig. 16) reveals an extended DIG layer

with individual plumes and faint filaments superposed. The disk emission is

composed of several distinct emission complexes, clustered basically in

three regions (nucleus + two regions within the disk), and some fainter

regions in the outskirts of the disk.

|

Figure 16. Continuum subtracted

H |

UGC12423 belongs to the Pegasus I cluster of galaxies, and was once

reported being one of the most massive and luminous spirals, with a derived

HI mass of ~ 9 × 109

M , and

logMH / LB = + 0.14

(Schommer & Bothun,

1983;

Bothun et al., 1982).

Hummel et al. (1991)

did not detect

extended emission from UGC12423 in their radio continuum survey.

Our H

, and

logMH / LB = + 0.14

(Schommer & Bothun,

1983;

Bothun et al., 1982).

Hummel et al. (1991)

did not detect

extended emission from UGC12423 in their radio continuum survey.

Our H image also does

not show any extraplanar emission. The galaxy

is almost invisible in H

image also does

not show any extraplanar emission. The galaxy

is almost invisible in H .

This can partly be attributed to

insufficient S/N, as we unfortunately only acquired one exposure for

H

.

This can partly be attributed to

insufficient S/N, as we unfortunately only acquired one exposure for

H , and also the R-band

image was not long enough integrated. This

needs to be re-investigated with more sensitive observations.

, and also the R-band

image was not long enough integrated. This

needs to be re-investigated with more sensitive observations.

4 http://www.roe.ac.uk/wfau/halpha/halpha.html Back.